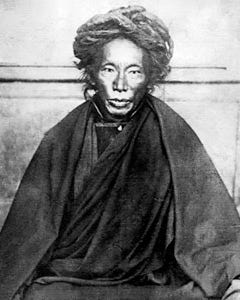

Sandor Berger

Sydney’s Great Eccentrics

Not every famous person has a name.

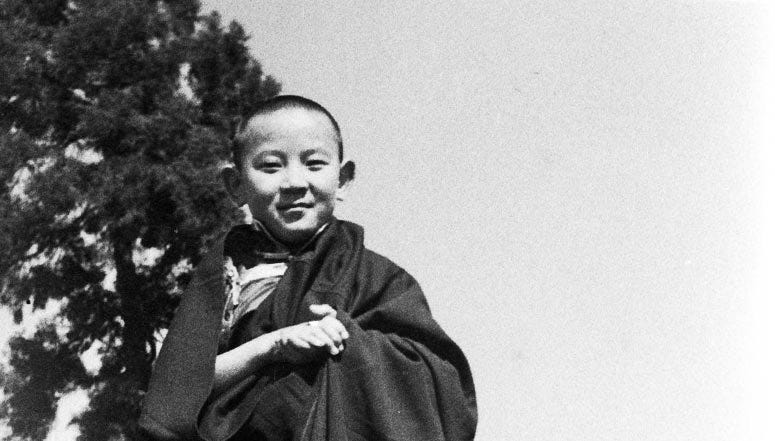

And almost no one knew the name of Sandor Berger, one of Sydney’s best known eccentrics.

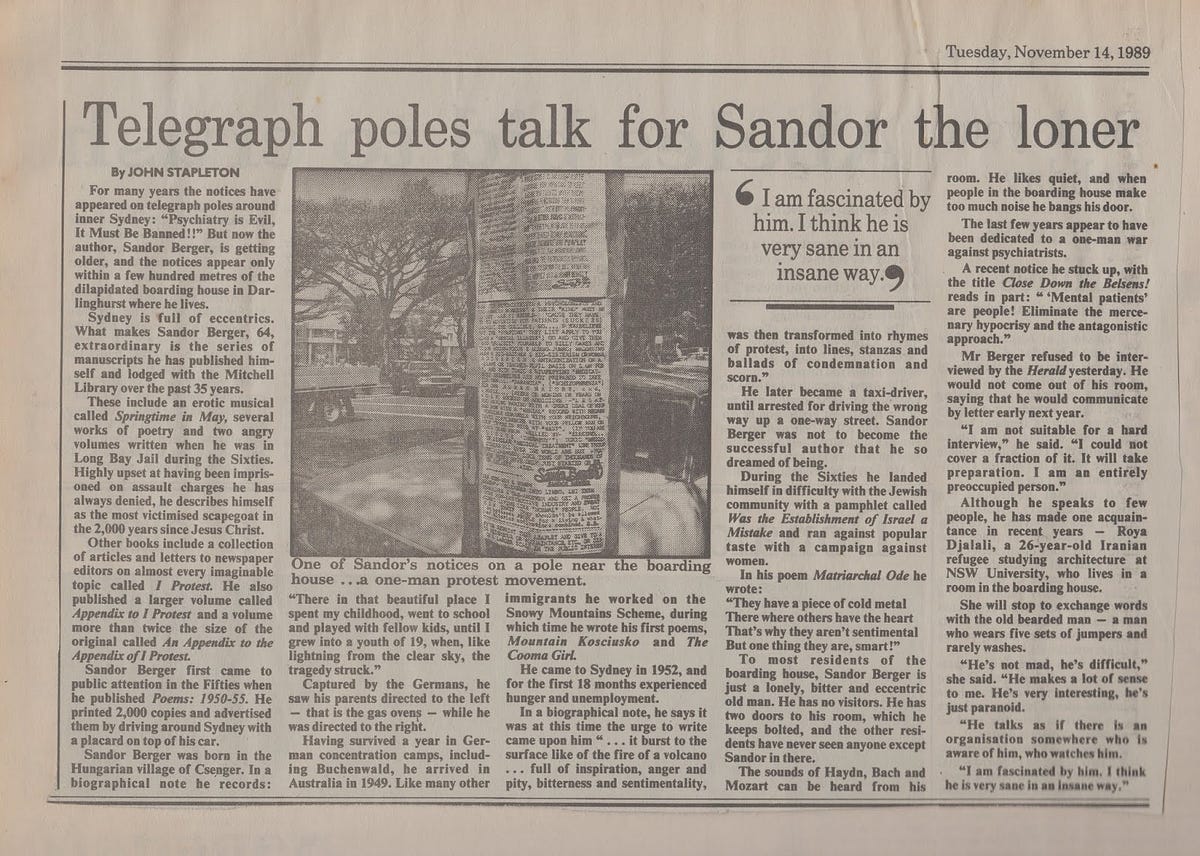

For many years notices appeared on telegraph poles across inner-Sydney: “Psychiatry is Evil, It Must Be Banned!!”

Everyone knew of him, nobody knew who he was, The Psychiatry is Evil man. You could hear people talking about him at parties, all of it speculation.

Sometimes, the story went, he was spotted as far afield as Parramatta Road, wearing placards and handing out leaflets.

Always with the same message: Psychiatry is Evil.

My guess: he was a survivor from the barbaric days of electric shock treatment.

But I did not know.

One of his notices titled Close Down the Belsens! read in part:

Mental patients are people! Eliminate the mercenary hypocrisy and the antagonistic approach.

We See Them in Glimpses

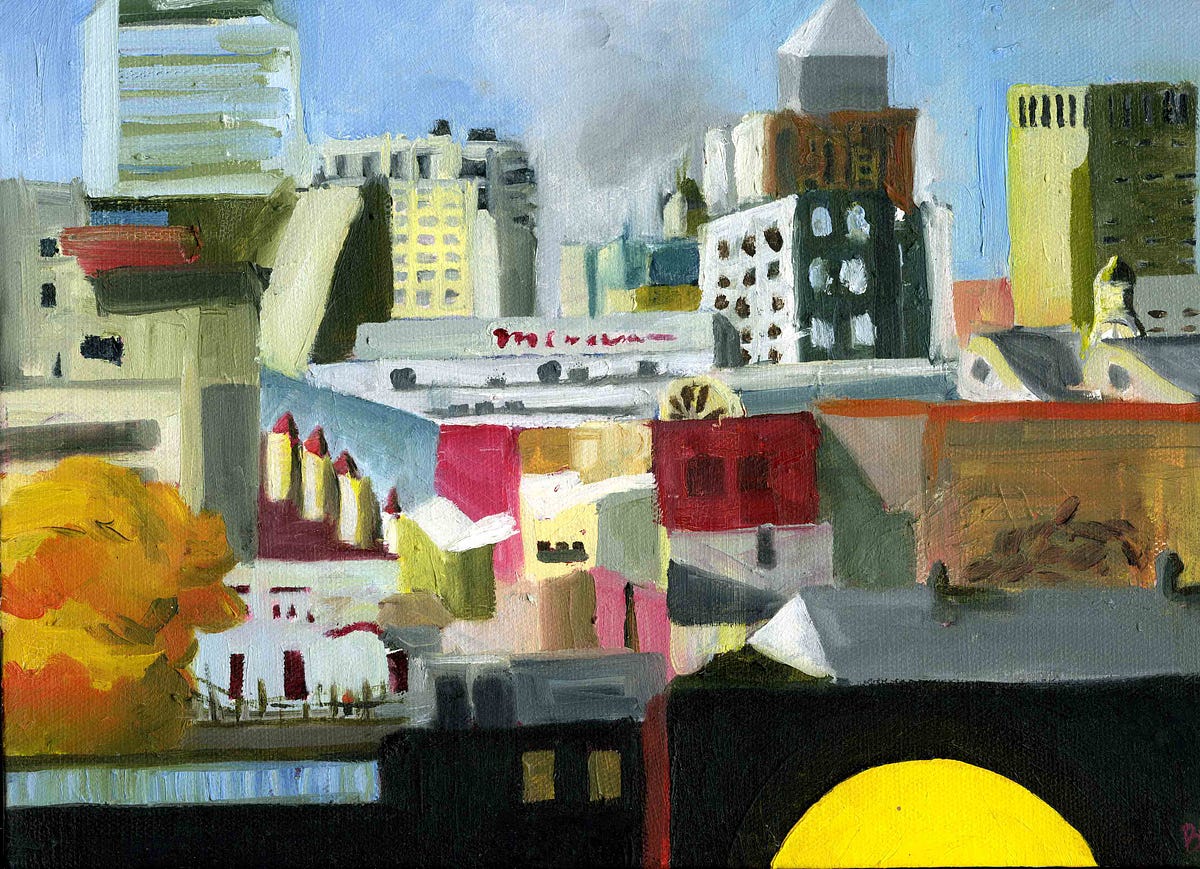

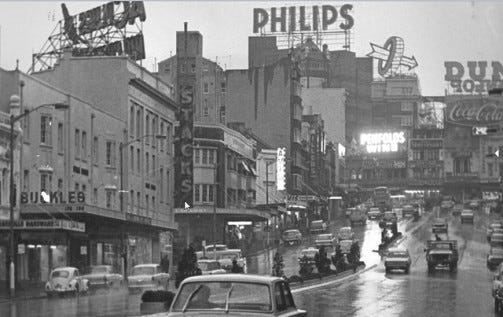

Sydney was full of eccentrics.

In a series on Sydney’s Secret history blogger Coffin Ed recalls sitting on the steps of the Town Hall watching three of Sydney’s most famous eccentrics converging each other.

The year was 1974:

Approaching from George Street south was the mysterious ‘knife grinder’, a man who had been pushing a metal box on wheels around the streets of Sydney for what seemed like an eternity.

Walking down Park Street was another offbeat character … who was famous for carrying and displaying a small Chinese fan whenever your eyes made contact.

From the north of George Street, directly outside the old Town Hall Hotel came Sandor Berger, poet, publisher and a crusader famous for the placard he wore attached to his chest which shouted “Psychiatry Is An Evil And Must Be Stamped Out”.

With an uncanny synchronisation of the traffic lights they came together for that fleeting moment in history on the corner of Park and George. Neither acknowledged each other and they simply disappeared into the night.

Eternity

Sydney’s best known eccentric is the “Eternity Man” Arthur Stace.

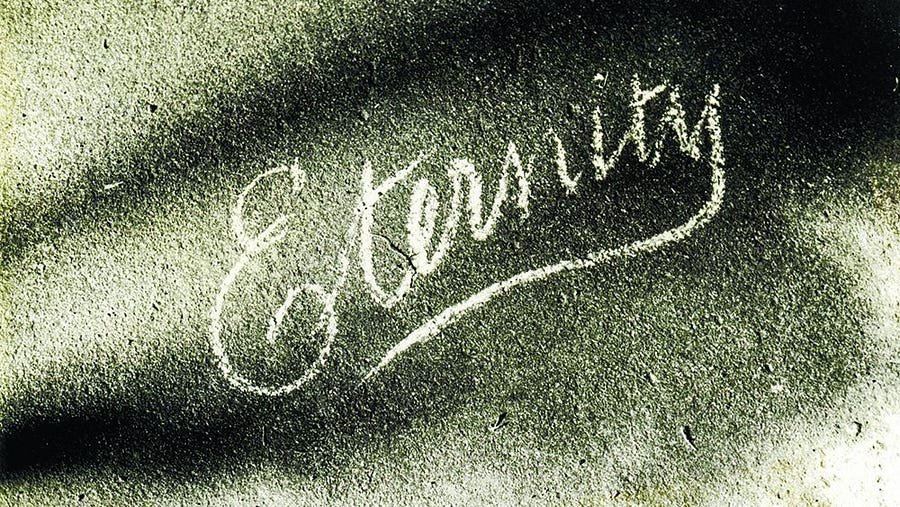

Beginning in the late 1940s, Stace began writing the one word “Eternity” on pavements across the central parts of the city, from Wynyard to Glebe, Paddington to Randwick.

Arthur Stace was born in Balmain in 1884 to a reputedly alcoholic mother and father. He overcame his own addiction to the bottle when he discovered the Church.

At one such meeting he heard the Reverend John Ridley shout:

“I wish I could shout eternity through the streets of Sydney.”

In recalling the day Stace said:

“He kept repeating himself and shouting ‘Eternity, Eternity’ and his words were ringing through my brain as I left the church. Suddenly I began crying and felt powerful call from the Lord to write ‘Eternity’.

“I had a piece of chalk in my pocket and bent down and wrote it.

“The funny thing is that before I wrote I could barely write my own name. I had no schooling and couldn’t spell ‘Eternity’ for a hundred quid.

“But it came out smoothly in a beautiful copperplate script and I couldn’t understand it and still don’t.”

Arthur Stace is estimated to have written the word half a million times before he died in 1967 at the age of 83.

In 2018, opposite the NSW Art Gallery, stencilled into the pavement, lies the following:

Nobody’s Business

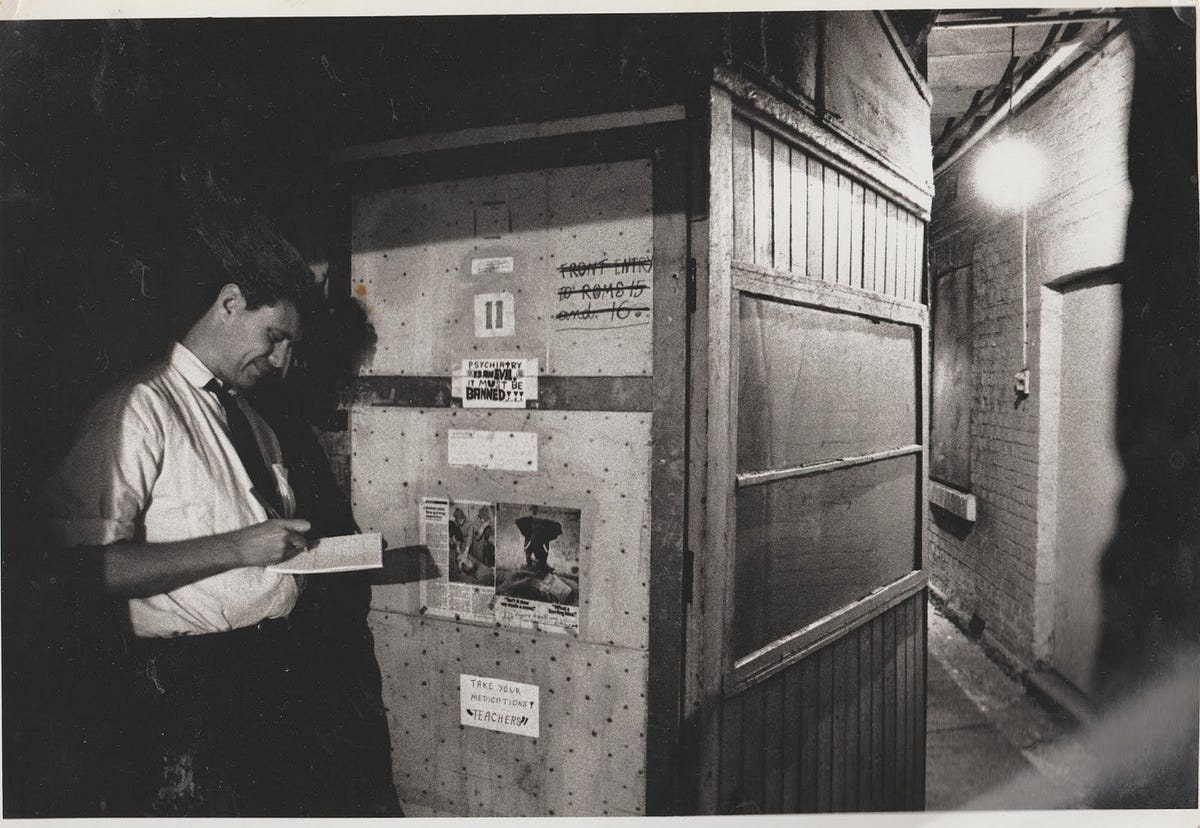

For reasons that are nobody’s business, back in 1989 I just happened to know well the dilapidated boarding house where Sandor Berger spent his final years.

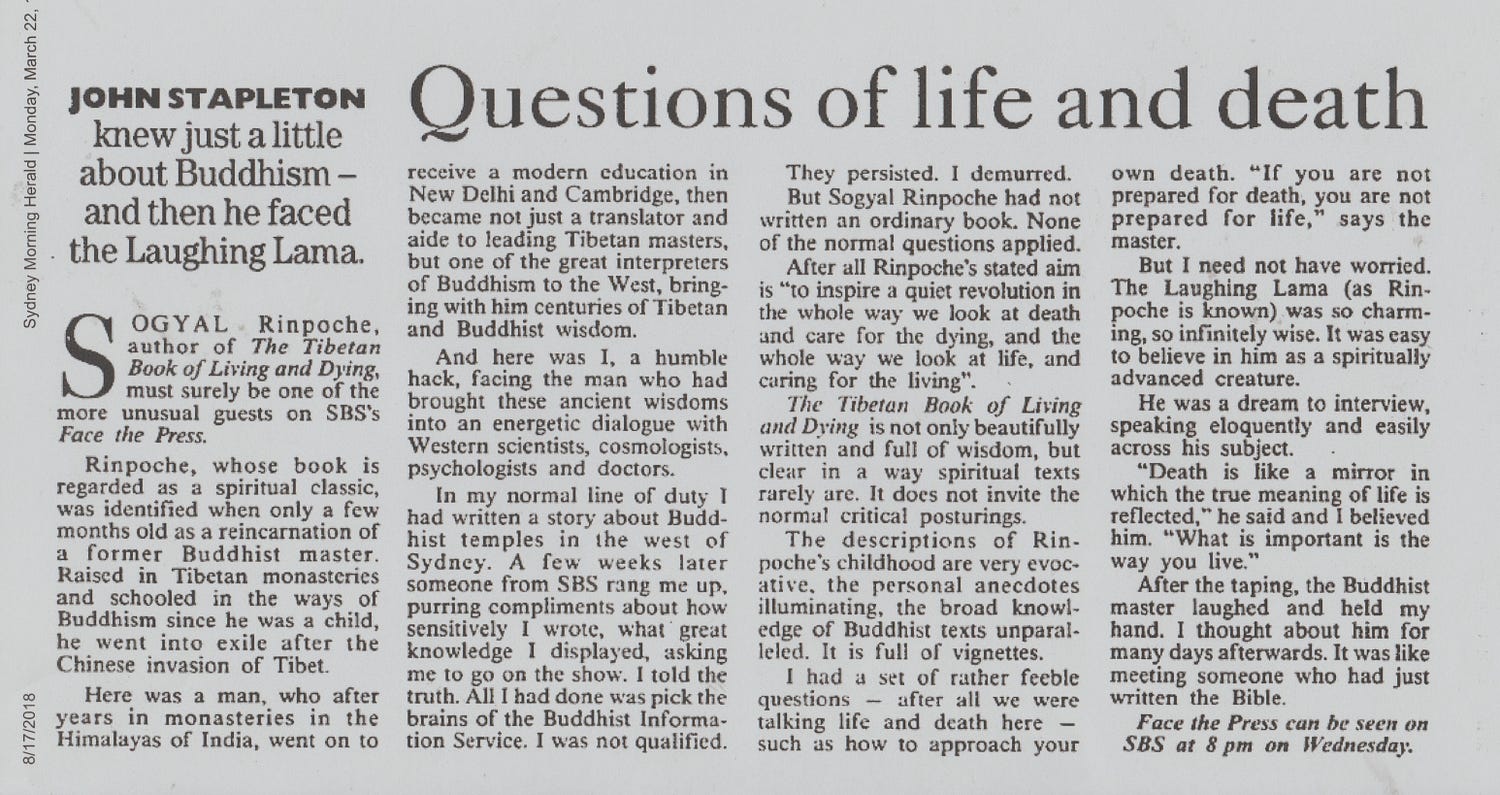

When I discovered the identity of the man in the room downstairs from where I used to visit, I became determined to do a story and pitched the idea to the Sydney Morning Herald’s News Desk where I worked.

Thus it was that I came, in official mode, to be pounding on Sandor Berger’s door. Photographer beside me. News car waiting for us in the street.

Ruins, of course, are always evocative and I was fascinated by a sense of decline. Even here.

Sandor Berger, then 64, was getting older, and the notices he had plastered all over Sydney now appeared only on a light poles within a few hundred metres of where he resided.

The interview did not go well. He refused to open his door.

But I was working, and could not return to the office empty handed.

“I am not suitable for a hard interview,” he said through his door. “I could not cover a fraction of it. It will take preparation. I am an entirely preoccupied person.”

Uniqueness

What made Sandor Berger particularly fascinating was that he lodged a number of vividly written self-published books with the NSW State Library.

He had a peculiar, highly pressurised type of consciousness, where he could hear things hundreds of metres away.

Unlike so many of the city’s invisible eccentrics, he left behind a record.

Amongst his works were a collection of letters and articles written to newspaper editors on almost every imaginable topic called I Protest.

He also published a larger volume called Appendix to I Protest. And a volume more than twice the size of the original called An Appendix to the Appendix of I Protest.

Sandor Berger also wrote two angry volumes written while he was in Long Bay Jail on assault charges in the 1960s.

The books resound with the sounds and brutality and bleakness of the prison and bitterness at his own sentence.

Highly upset at being imprisoned on assault charges he has always denied, he described himself as the most victimised scapegoat in the 2,000 years since Jesus Christ.

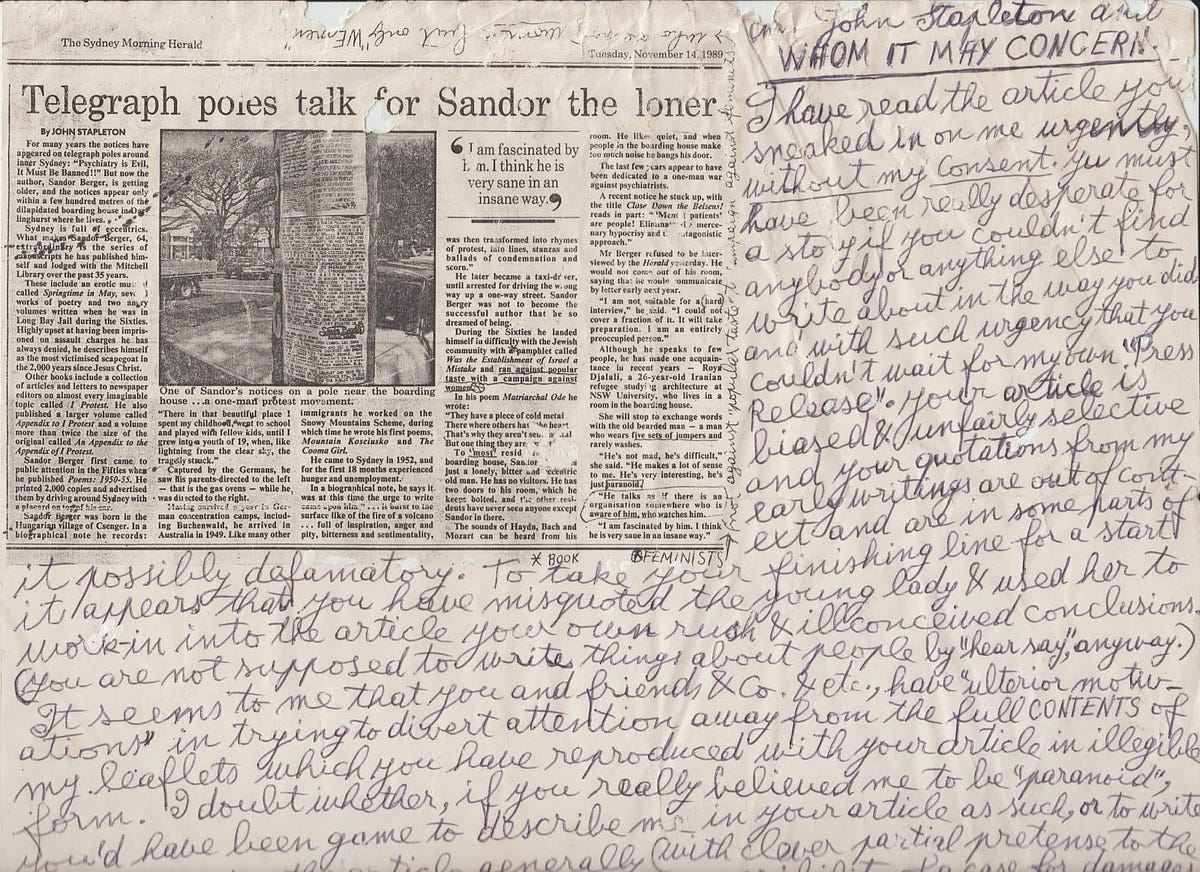

Sandor Berger’s Response

Many of the people I wrote about never read newspapers, and never read what I wrote.

But Sandor Berger was an exception. He was incensed.

Which saddened me because, in a sense, the piece was a mark of appreciation

With the article photocopied into the corner of a large sheet, he wrote:

I have read the article you sneaked in on me urgently, without my consent.

You must have been really desperate for a story if you couldn’t find anything else to write about in the way you did and with such urgency that you couldn’t wait for my own “Press Release”.

Your article is biased and unfairly selective and your quotations from my early writings are out of context and are in some parts of it possibly defamatory.

Sandor Berger concluded:

It is obvious that at best you seek to ridicule … to divert attention away from the contents … and to alienate the author & discourage people from reading…

Sandor Berger grew up in the Hungarian village of Csenger.

In a biographical note he records:

“There is that beautiful place where I spent my childhood, went to school and played with my fellow kids, until I grew into a youth of 19, when, like lightning from the clear sky, the tragedy struck.”

Captured by the Germans, he saw his parents directed to the right — that is to the gas ovens — while he was directed to the right.

Sandor arrived in Sydney in 1952, and wrote that it was during his first 18 months of hunger and unemployment that the desire to write came upon him:

“It burst to the surface like the fire of a volcano … full of inspiration, anger and pity, bitterness and sentimentality, was then transformed into rhymes of protest, into lines, stanzas and ballads of condemnation and scorn.”

Sandor Berger died in 2006 at the age of 81.

The boarding house where he once lived, and shouted at me through his door, is now a prestige property.

The Sydney he once knew and fought against is barely recognisable.

Adapted for Medium from the upcoming book Hunting the Famous.

Based on articles first written for The Sydney Morning Herald.

John Stapleton worked as a staff reporter for The Sydney Morning Herald from 1986–1994 and for The Australian from 1994–2009.

A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.