Defective Modelling Throws Lockdowns into the Dustbin of Credibility

By Professor Ramesh Thakur

On 26 May, Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy said if Australia’s mortality rate matched the UK’s, we’d have had 14,000 Covid-19 deaths. This is just tautological rubbish. It would be just as true and equally pointless to say if Australia’s mortality rate matched Vietnam’s, we’d have zero deaths.

The Australian modelling, done by the Doherty Institute, proved to be as defective as the ICL and Swedish modelling. Although it was delivered to cabinet as case numbers began to rise in Australia and informed their decision to close borders and impose Stage 3 lockdown measures on 20 and 30 March respectively, the modelling was not released to the public until 7 April. Earlier, speaking in Canberra on 16 March, Deputy Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly said up to 150,000 Australians could die from the coronavirus under a worst case scenario of 15mn infected cases with 60% of the population being infected, and up to 50,000 dead out of 5mn infected with 20% of the population being infected. ‘The death rate is around 1 per cent. You can do the maths’. ‘This is a horrendous scenario’, Brendan Murphy said. ‘A daily demand for new intensive care beds of 35,000-plus’. The figures were based on a combination of Chinese and international data since the beginning of the pandemic’s spread in December. ‘It proves the theory of flattening the curve’, PM Scott Morison said.

They might want to redo their maths. The modelling shows that under an unmitigated worst case scenario, 89% of the Australian population could have been infected. In that scenario only 15% of those who needed intensive care would have been admitted.

All these assumptions, derived from the core assumption of the reproduction rate ‘R’ being 2.53% based on the initial Wuhan data, have proven to be speculative, unreliable and inflated. As it turned out Australia’s ‘R’ was below 1% already by the time that strict control measures were put in place in late March.

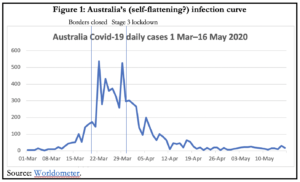

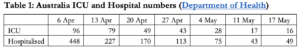

The highest tally of daily cases was 528 on 29 March; of ICU beds occupied was 96 on 6 April; and of Covid-19 patients in hospital was 448 on 6 April (Table 1). Stage 3 lockdown measures were imposed on 30 March. One week later the daily new cases had fallen below 100 and has stayed there, with the sole exception of 9 April when it was exactly 100. In interpreting the figure, it bears repeating that the virus has a 5-7 day incubation period.

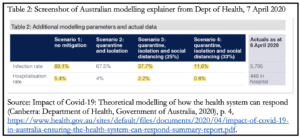

Table 2 is a screenshot of the table from Appendix A of the modelling published by the Government on 7 April. It may be the only objective check we have on assessing the accuracy of the modelling.

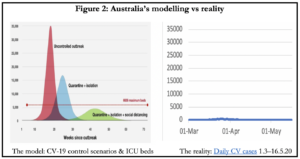

Under the model’s best case Scenario 4, with tight quarantine, isolation and social distancing measures in force that reduce the rate of transmission by a third, 2.9mn people would be infected, 200,000 would require hospitalisation and nearly 5,000 people would need to be in intensive care (Figure 2) during peak demand.

With infections just over 7,000 and ICU peak occupancy at 96, the predicted numbers are off by 400-fold and 50-fold respectively.

If their best case scenario is this defective, there’s little reason to believe the other, including worst case, estimates of the modelling. Thus there’s no accurate measure of how many lives were saved by this level of intrusive state control.

Taking advantage of the recommended lockdowns, a surprising number of political leaders seem to have relished the opportunity to indulge their inner despots, and some police officers took advantage early on to indulge their inner bully.

Queensland’s Chief Health Officer banned RAAF flyovers for ANZAC Day by four pilots despite admitting they would have been no risk to themselves or anyone else but would set a dangerous precedent, while permitting up to 80 to congregate for an Aboriginal Elder’s funeral. Her logic on school closures is similarly idiosyncratic. She accepts the evidence that schools are not a high risk environment for the spread of the virus but closing them helps to convince people how grave the situation is:

‘So sometimes it’s more than just the science and the health, it’s about the messaging’.

Almost all journalists seem to have lost their cynicism towards claims by the authorities and instead become addicted to pandemic panic porn.

The measures taken have been extreme, more even than has been done during a war and more than was attempted during earlier, deadlier flu epidemics. The authorities have told us who and how many are permitted into our homes, where we can and cannot go, how many people we can meet, where we can shop and for what, which services we can access and which not, even which medical and dental services we can still access. Who is going to call the Governments and the medical experts to account for the overreach?

A critical and sceptical profession would have put the government’s and modellers’ claims under the blowtorch and subjected them to withering criticism for the magnitude of errors by which their predictions have been off. Instead they have mostly joined the adoring multitudes in showering praise on the magnificence of the emperor’s new robe. Or, to change the metaphor, it is as if the Wicked Wizard of Wuhan (WWW) has cast an evil spell over the whole world and turned it into an enchanted forest with humans confined to limited spaces and the other creatures roaming freely, no longer terrorised by homo sapiens.

Looking to the future

Australia’s 50th biggest cause of annual deaths (110) is poisoning. At present, that is, Covid-19 does not make it to the top 50 causes of deaths. And for that we have inflicted such damage on people’s lives, livelihoods, education, freedoms, condemning them to house arrests en masse and robbing so many young of their future? If ever there was justification for a Royal Commission, this is it.

The point of the inquiry should not be to apportion blame for past mistakes. Rather, its primary term of reference should be to identify how we can prepare better for the next big one. In retrospect, we could have used the good fortune of the virus arriving in Australia in the latter part of summer, instead of in the middle of the flu season as in the northern hemisphere, to boost surge capacity at every bottleneck point to test, isolate, trace and treat cases.

One way or another, we will come out of this pandemic. But we can also be absolutely certain that it will not be the last pandemic to hit us. There will be others and next time we may not be fortunate in the timing (off flu season) or the geographical epicentre (North Atlantic). Also, the choice of Commissioners should reflect modern Australian demographics and the already evident reality that the best lessons to be learnt for successful responses are from Asia–Pacific countries. It’s both perplexing and irritating that, reflecting the composition of political and bureaucratic elites, Australia continues to look to Western countries to establish benchmarks.

Subject to change as the virus evolves, some things I would like to see begin with putting hard lockdown into the dustbin of history. And state border closures too, for that matter. Related to this, the government should provide the best available information and guidelines for individual and social health practices, but transfer the burden of risk back to individuals for assessing the dangers to themselves and the appropriate preventive measures to take and practices to adopt. A smarter approach is a more targeted approach, especially for an epidemic that is so strikingly age and gender stratified and in many jurisdictions has hit care facilities particularly badly.

We need surveillance mechanisms to identify and quarantine outbreak clusters backed by reliable contact-tracing methods. A team of scientists from Edinburgh and London has suggested a segmenting-and-shielding strategy that segments the elderly and frail while shielding their carers with adequate personal protective equipment. It is adapted from the ‘cocooning’ of infants by immunisation of close family members that is a pillar of infection prevention and control strategies.

The one thing in common that all the successful Asia-Pacific examples – Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore – have is they learnt from the earlier avian flu and SARS examples. They made preparations in advance and their institutions and procedures were activated with exemplary swiftness and efficiency. We certainly require prepositioned and pre-approved equipment and procedures for screening passenger traffic at air and sea ports on short notice, stocks of protective, preventive and therapeutic equipment and supplies, a surge capacity to break through the bottlenecks when we need to scale up, and the right balance between national manufacturing capacity and diversified global supply lines.

How can we best begin organising for the next health epidemic by way of institutions? The National Cabinet has been a good innovation. But we also need the equivalent of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Like the latter, I’d be in favour of a Trans-Tasman centre (TTCDC).

This story was originally published in one of Australia’s leading social policy journals Pearls & Irritations and is reproduced here with their kind permission.

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS