The Photography of Palani Mohan

Every year their numbers drift inexorably towards zero.

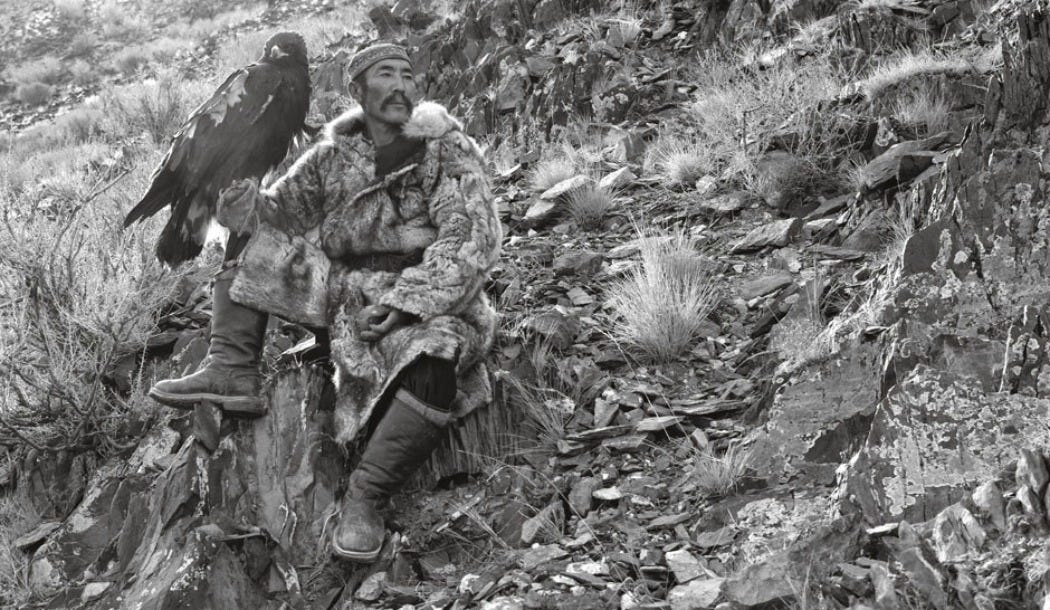

Deep in the wilds of far western Mongolia are the last remaining Kazakh eagle hunters. The burkitshi, as they are known in Kazakh, are proud men whose faces echo the harshness of the beautiful, barren landscape they call home.

They have a remarkable bond with the golden eagle, which to them represents the wind, the open space, the isolation and the freedom found at the edge of the world.

Australian photographer Palani Mohan has spent years documenting the noble hunters, but says only 60 remain, and fears the ancient tradition could disappear within 20 years. Along with them perishes a unique way of life.

Young people are uninterested in the tradition and increasingly migrating to cities, like the polluted Mongolian capital of Ulan Bator.

Here are excerpts from the Hunting With Eagles: In the Realm of the Mongolian Kasakhs and samples of Palani’s magnificent photography.

During the long winters, the eagle hunters leave their homes and head into the mountains on horseback to hunt foxes — a tradition said to stretch back as far as 940 AD.

This way of life, which has lasted for centuries, is rapidly disappearing.

“There are about 60 of the true hunters left, and each winter claims a few more because winters are incredibly brutal. And they’re getting old, and every winter about two of them die,” Mohan says.

“It’s important not to forget about people like these eagle hunters on the edge of the world.”

It is not just the bitter cold threatening to wipe out the eagle hunters.

“I’ve spoken to a lot of teenagers, men and women, and they want to wear jeans and go into town and listen to music and earn money. The eagle hunting is a lonely, cold, old way of living and like all teenagers they want the new modern thing,” Mohan says.

“Ulaanbaatar, the capital, is a very long way away but that’s where a lot of people head. People are going to Russia or Kazakhstan.”

Mohan, who was born in India and grew up in Australia, cut his teeth as a cadet with The Sydney Morning Herald. It was then that he first saw a photograph of an eagle hunter.

“Where on earth was Mongolia, and how could men tame eagles? I was desperate to go, but for 25 years I did nothing about it.”

But finally Mohan set out to photograph every remaining Kazakh eagle hunter.

“At first it’s cold and there’s no-one there, and it’s very desolate. Eventually after many days of asking people you find one,” he says.

“One eagle hunter would take me to another eagle hunter, and so it goes. But sometimes you have to drive for a couple of days to find the eagle hunter.”

He thinks he has fulfilled his dream of “finding them all”, though admits “you can never be sure”.

Mohan found the solitude and space of Mongolia very affecting, but that was not the only challenge.

“I hate the cold, and I am mainly vegetarian, so I was all wrong for this job. It’s by far the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do physically, and professionally,” he says.

“It is -40 degrees, it’s Hell on Earth. My eyes were constantly watering, which in turn would freeze, and it’s very painful.

“And my camera gear would completely collapses. Batteries have a real issue with the cold. I used to go to sleep with the batteries taped to my armpits and other warm parts of my bodies, just to keep it warm.

“When I needed to shoot I would stick my hands down my shirt and rip out the battery, and it would have hopefully a couple of minutes before the battery completely drained.

“And its very difficult to work with six pairs of thermal stuff on, and big jackets on, so it’s hard work. It’s very difficult to operate gears and buttons and cameras and so on.”

But he says the pain was worth it if his photos help people remember “people like these eagle hunters on the edge of the world”.

“It is the bond between hunter and eagle that fascinated me,” Mohan writes in the book. “All the men I’ve spoken to describe the eagle as part of the family, even as their own child. The hunters all had stories about how they loved all their birds even more than their wives. And there’s a Kazakh saying that if a hunter’s father dies on the day the snow starts to fall, the hunter won’t be at the funeral because he’ll be up in the hills with his eagle.”

This intense relationship begins when a hunter takes an eaglet from its mother and back to his own home, promising to “love [the eagle] as his own.” There, he shrouds the bird with a leather hood (tomaga) to keep it calm, and begins hand-feeding it horse and yak meat. Once the bird learns to trust its feeder, it goes on its first hunt, which Mohan describes in the book.

The golden eagle is a perfect predator, with an awe-inspiring [eight-foot] wingspan. A fox is easy prey, and when hunting in pairs, eagles are capable of bringing down a wolf.

The birds are calm and exude confidence when they head into the hunt. After the tomaga is lifted from its head and it sees the fox in the valley below, the eagle takes its time waiting for the right moment. Then, without warning, it will raise its wings and dive like a bullet, leaving a rush of air in its wake as the hunter makes a screeching sound, urging it on.

Within moments the eagle reaches its prey, sinking its claws through the fur and skin. Fox meat makes a welcome winter meal for the hunter and his family, while the pelt is kept as a trophy or made into hats and other items of clothing.

Golden eagles live till around 30 years of age, and are released back into the wild at about 15.

The hunters and their families wear their fur pelts proudly, along with elaborately embroidered robes and coats.

Golden eagles are like no other bird. They want to be with you. They love you. And they love to kill for you.

When the time comes to let them go, it’s the hardest thing a man can ever do. … I’ve had more than 20 eagles in my life. Last year I released my last eagle back into the mountains. It was as if a member of my family had left. …

This tradition is dying, and there are fewer and fewer old hunters these days. You can have an eagle, but that doesn’t make you a hunter.

In the old days, if you didn’t have an eagle next to your home you weren’t a real man. …

The young generation today aren’t interested, and there are many things that keep them busy, such as earning money and listening to music.…

We should train our children to keep this tradition alive. This is who we are. To the young I would say: the golden eagle is a holy bird; treat eagles as your children. Love and respect them. If you do this, they will give everything back to you.

RELATED SITES:

EXTENDED RADIO INTERVIEWPalani Mohan

The last eagle hunters of Mongolia through the lens of Palani Mohan.www.abc.net.au

PALANI MOHAN’S WEBSITEPalani Mohan – Photographer

Palani Mohan is an award-winning photographer based in Hong Kong.www.palanimohan.com

Written and compiled by John Stapleton, editor of A Sense of Place Magazine. A collection of his journalism can be found here.

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS

Dunghutti activist Paul Silva

Dunghutti activist Paul Silva Elizabeth Jarret MCing at the rally

Elizabeth Jarret MCing at the rally

The March for Justice

The March for Justice

Gomeroi activist Gwenda Stanley demands tangible change

Gomeroi activist Gwenda Stanley demands tangible change