They blame climate change. They blame the drought. They blame everyone and everything but themselves.

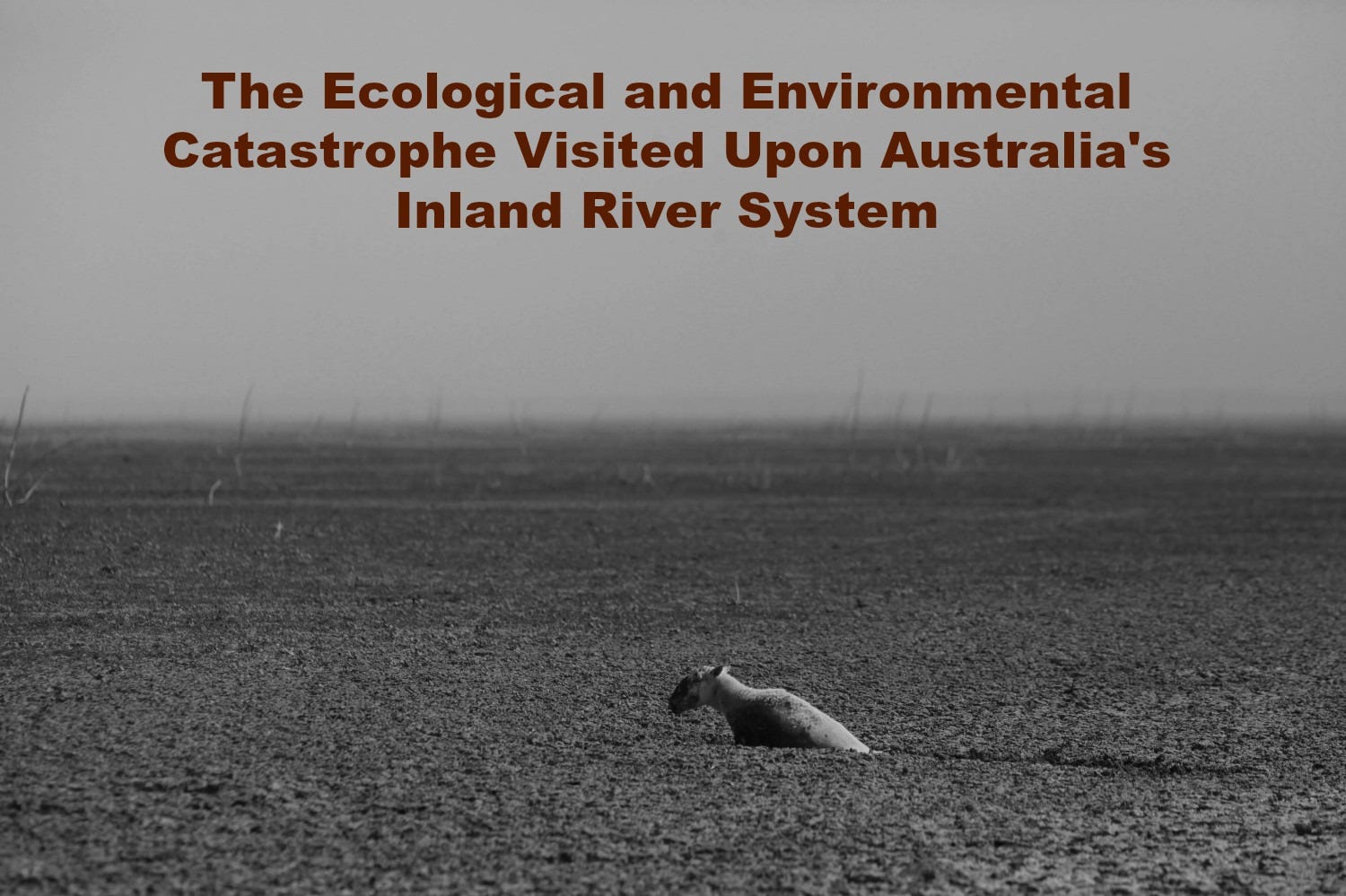

The stench of millions of dead fish, the rotting corpses of kangaroos and sheep, the missing bird life, the farmers who can no longer farm, devastated indigenous peoples, an ancient, desecrated landscape, internationally significant wetlands nothing but dust bowls, all of this and more is happening across Central Australia — right now.

Decades of chronic government mismanagement and corporate greed have turned Australia’s most significant and extensive river system, the Murray-Darling, into a disaster of national and international significance.

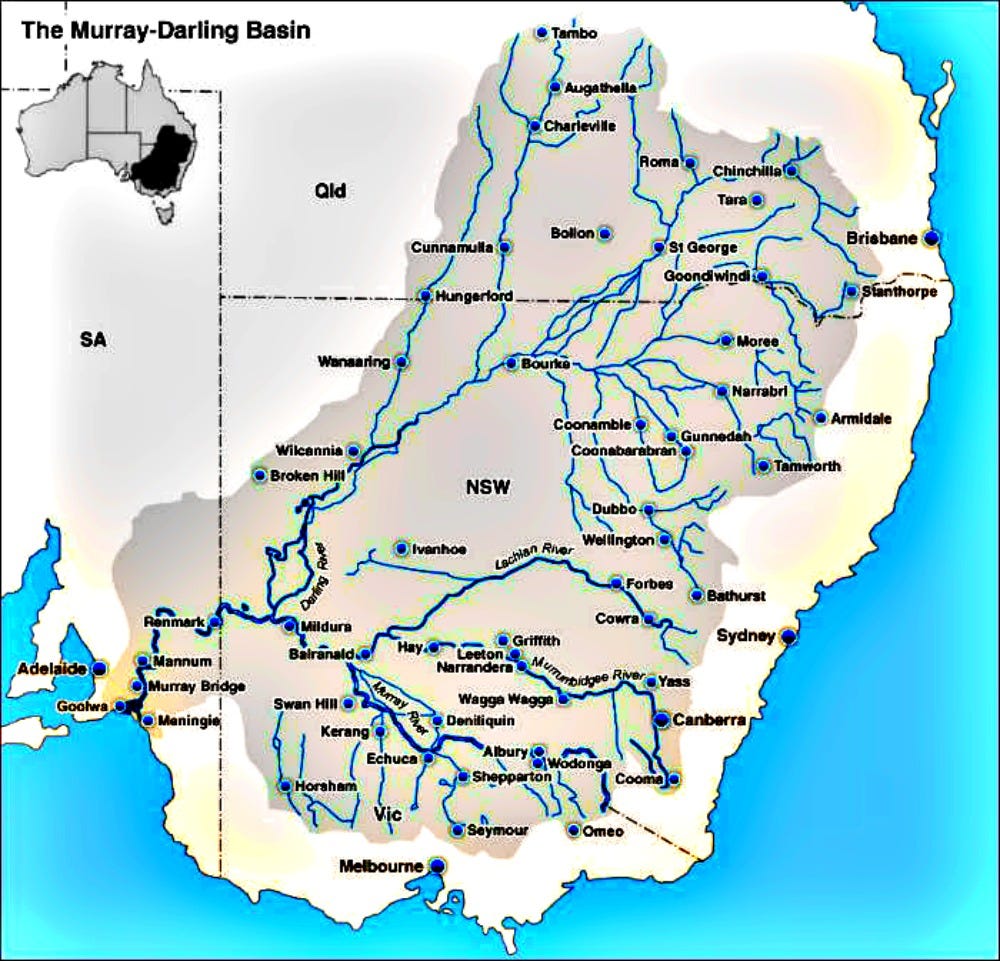

The Murray Darling Basin covers more than a million square kilometres, draining some one seventh of Australia’s land area.

The meandering, often intermittent rivers that feed into the Murray Darling stretch across more than 3,700 kilometres and for much of their length flow inland.

They are unique in the world.

Australia’s hapless political and bureaucratic castes have squandered billions of dollars purporting to be environmentalists who care about the fragile ecosystems of the country’s arid and semi-arid inland.

If you want to understand the underlying causes of mismanagement and administrative chaos, it is usually a case of just follow the money. And so it is in this case.

Turning public assets into private gain has reached new heights in Australia.

The outgoing conservative government, on the nose in the electorate and facing electoral wipeout in May, if it lasts that long, has a sour reputation as a pack of corporate crooks who have misused their political positions to plunder the public purse.

The debacle visited upon a great swathe of the country is a case in point; the toxic blue green algal blooms poisoning once flowing rivers is a perfect analogy for a government in terminal decline.

Make no mistake: this situation is highly political and the incumbent conservatives are facing the full wrath of the electorate at both state and federal levels.

As senior editor at The Canberra Times Jack Waterford puts it, the dead and stinking fish are:

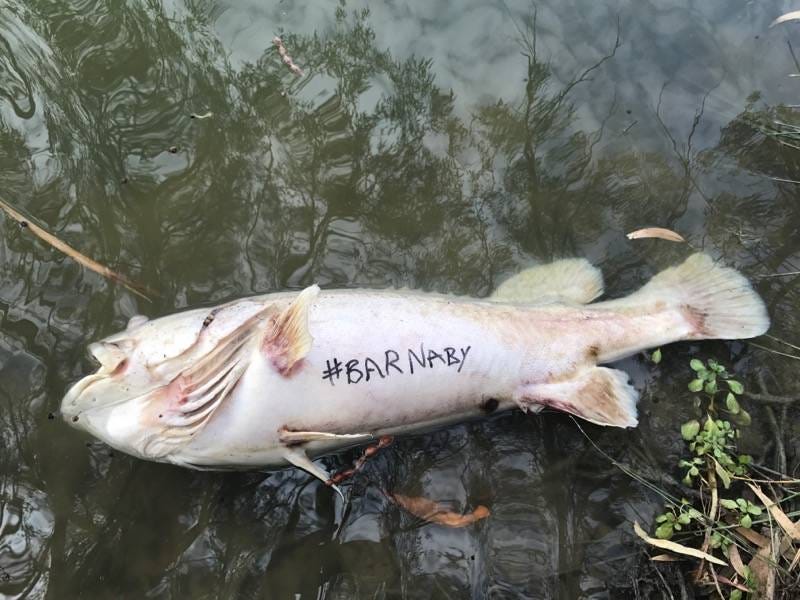

A floating monument to greed, corruption, maladministration and disastrous environmental management.

The opportunists who gifted water rights to irrigators are despised up and down the entire river system.

Bureaucratic empires have been built around the notion of sensitive environmental and water management of the inland river system.

But it was Big Money — the cotton and irrigation industries — which won the day.

There Are Many Beginnings To This Story

There is history; decades of history. And there is the terrible present.

Only a few days into 2019 news of a massive fish kill in the Menindee Lakes complex in far western New South Wales hit the headlines and news bulletins.

There is a mountain of evidence; at first only posted by local pastoralists, soon to be taken up by the nation’s media.

The owners of the historic Tolarno Station have been amongst the most prominent activists, alerting the public and the media to the extent of the disaster.

The video below went viral, attracting millions of views and thousands of comments and shares.

These are not your run-of-the-mill activists. It takes a lot to turn the normally taciturn graziers and residents of Central Australia into political animals.

But turn they have.

Owner of Tolarno Rob McBride told A Sense of Place Magazine, on the day of yet another fish kill:

It’s going to get worse before it gets better.

This is nothing to do with drought. This is government policy, both State and Federal.

It has everything to do with greed, corruption and money.

This is a cataclysmic destruction of a river system.

For us there is no surprise.

Bureaucrats and politicians have done everything they could to undermine any integrity in the system. They should be held accountable for the destruction of the environment.

McBride said the public had already funded schemes, to the tune of $8 billion, to put water back in the river system through buybacks and government incentives.

Where is the water?

Where is the audit of where the money went?

The water went straight to cotton irrigators, absolutely.

People should go to jail over this. Absolutely.

People the world over need to understand that this has nothing to do with nature. These fish are dying in their millions because the system has been destroyed.

It has nothing to do with nature and everything to do with money.

Award winning news photographer Dean Sewell, who has recently toured the area and whose work is featured throughout this piece, says:

While all the news has been on the million dead fish in Menindee, upstream they’re already dead.

Hundreds of kilometer strips where all the fish are dead. There is no water up there. And what water there is has turned green and putrid.

Locals have prepared the following video as a way of explaining the catastrophe to an international audience.

Bill Johnson, a well respected environmental water management expert who previously worked at the Murray Darling Basin Authority and has been touring the affected areas, told A Sense of Place Magazine:

To describe what is happening here as an ecological and environmental catastrophe is understating what is going on. It is deeply serious.

This is the latest sign of complete catastrophic failure.

It has been heading this way for decades. This is a failure of water allocation policy. For all the talk, the endless meetings, consultations, inquiries and reports, rivers like the Darling should have come first.

It is not possible to remedy the situation around Menindee at present. Even heavy rains in the upper catchment will take months to arrive, even if we can persuade governments to let the water through rather than it being taken by the massive irrigation projects that line the length of the river.

Menindee is one of the last major breeding sites on the Darling River remaining for a number of freshwater fish. For the fish dying in those waterholes there is nothing that can be done.

Mr Johnson said there was no water in the upstream catchment and fish were in strife across the Murray Darling Basin.

There have been fish kills in the Namoi River, the famous Macquarie marshes and at Inverell.

There will be more kills.

Mr Johnson said the government had declared it would hold an inquiry into what killed the fish.

Yet another inquiry!!

We know what killed the fish.

One of the things we still don’t know is how much water is being taken out of the river, 99% of it by cotton irrigators.

No one will acknowledge how much water is being used.

That can only be because people don’t want to know.

A Wonderland At Risk

Twenty eight years ago, as a staff reporter for The Sydney Morning Herald, I wrote a cover story for the paper’s weekend colour magazine, Troubled Waters: A Wonderland at Risk.

Even then, it was obvious trouble was brewing. One of the cores of the scandal that has now unfolded lies with the unique networks of ephemeral lakes and intermittent rivers which characterize the arid interior.

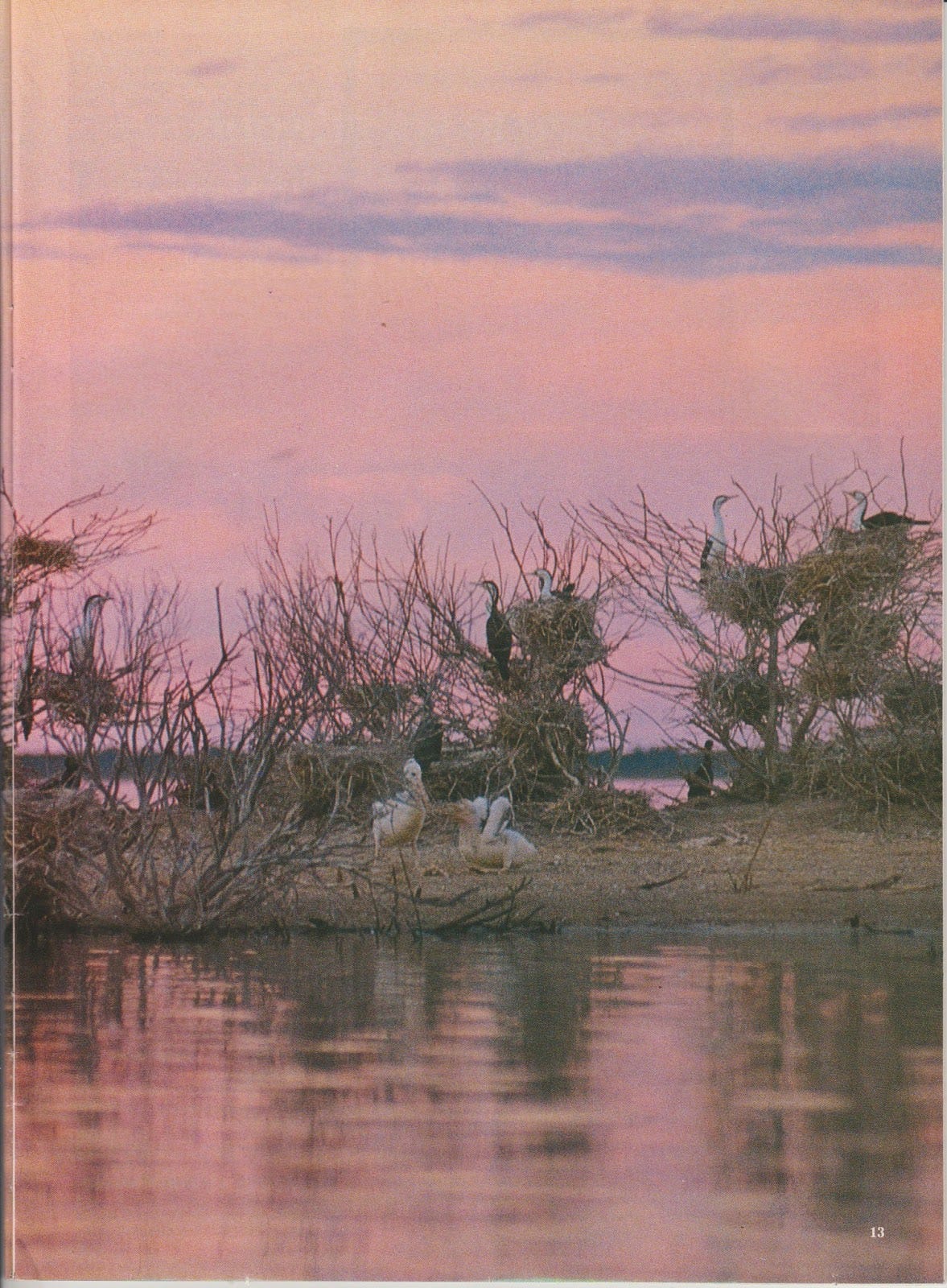

Scientists believe they are looking at the remnants of an ancient lake and wetland system which ran through the centre of the continent during wetter epochs. Hence the remarkably high number of birds the lakes attract.

As the land dried the birds adapted, being able, in one of the great scientific mysteries, to be able to detect water across hundreds of kilometres of arid land and to move between water sources.

Skeletons of an extinct breed of fresh water dolphin, along with flamingos, have been found in central Australia.

While they did not make the adaption to a drier climate, many other species did, flying from one ephemeral lake to another across vast distances.

Twenty eight years ago I wrote:

Some attract waterbirds in numbers that make them the equal of the spectacular flamingo lakes of Africa and the migratory wetlands of Europe and North America. The density of bird life is two or three times that of Kakadu: 100,000 birds of more than 30 species may inhabit a single lake only a few kilometres long. Spoonbills and cormorants nest in drowned trees, colonies of pelicans rear their young on sand islands and banded stilts nest in shallow scrapes on the ground. Darters, herons, ibis, egrets, sandpipers and ducks mingle with flocks of black swans.

But all this is changing and the scandal is while Australia actively promotes international conventions to protect waterbird habitats, we simply do not know what impact human activity is having on our semi-arid wetlands.

Basic research is nonexistent: We do not know the impact of the cotton industry. Australia’s most profitable legal agricultural activity is spreading rapidly westwards with its attendant chemical runoff and manipulation of river systems.

Now We Know

Writing in The New Daily, senior journalist Michael Pascoe records that while spectacular fish kills creaste focus on a particular problem:

Steady degradation just eats away at the entire environment in that tricky way nature has of everything being connected.

The fish in their rotting riverside masses are extremely photogenic, at least from a news point of view. Their stink sparks predictable political blame games and, at least for a while, calls for action.

Yet the headline-grabbing dead fish have come late to the Murray-Darling ecological disaster story.

It’s much harder to focus outrage on something that’s not there, something that can’t be photographed. But like the dog that didn’t bark, the birds that are not there still bear powerful witness.

The disaster of missing birds has been rolling on for years, not that the relevant federal ministers doing the water deals seem to have cared.

This is government incompetence, pure and simple.

Professor Richard Kingsford, Australia’s most experienced and meticulous scientific expert on the bird life of Australia’s interior, spearheaded a University of New South Wales study which found that water bird numbers in the Murray-Darling basin were down about 70 per cent over the past three decades.

The birds have either died or they haven’t bred as much as they did in the past.

We separated that group into all of the birds that eat fish, all of the birds that eat invertebrates and vegetation, and what we’re seeing is that all of those groups are also declining, which tells you the whole of the ecosystem is in decline.

The Political Response: Shameful

The New South Wales Minister for Regional Water.

Seriously?!

Paid four times the average wage, Niall Blair appears to have been doing little if anything to earn his money.

Local Menindee resident Graeme McCrabb says despite the size of the fish kill no one from the Federal Government or the Murray Darling Basin Authority have visited.

This is the biggest environmental catastrophe in the history of the river, and no one is here. It beggars belief.

Niall Blair did visit, but toured what is left of the river by boat and did not meet locals, claiming police advised him of safety concerns.

The word on the ground is that the police offered no such advice.

As 150 locals gathered to meet him, Blair roared by at 40 knots in a speedboat — all around him the stench of dead fish.

And his stinking, sinking career.

Compounding the outrage, Blair failed to front or even phone in to a meeting of mayors from towns along the embattled Barwon-Darling river system who gathered at the government’s ministerial headquarters in Sydney to discuss the water crisis.

How truly, utterly, inexcusably gutless.

The mayors had traveled more than 1,000 kilometres to be there — at taxpayers expense. They were expecting to meet the responsible Minister, Niall Blair.

In the world’s driest continent, the Nationals, the party which has traditionally represented the interests of country people, are being directly blamed for selling off the inland’s scarcest and most valuable resource, water, to the cotton industry.

Hated up and down the river system, former Deputy Prime Minister, the National Party’s Barnaby Joyce, is directly in the line of fire after his scandal plagued period as Federal Water Minister.

Straight off, the dead and stinking fish symbolize the mismanagement, maladministration and corruption of water policy in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria.

It doesn’t take a great deal of extension to work it into an argument about the National Party’s intellectual and moral bankruptcy, particularly under former leader Barnaby Joyce, and its complete unfitness to govern.

Rural folk increasingly feel that way, wondering how a party established to represent rural and regional Australians became instead available for rent to big mining interests, the coal industry, the fracking industry and large-scale agribusiness, particularly when these interests threaten their livelihoods.

Jack Waterford. The Canberra Times.

As we said, there’s history, plenty of history.

Laughably former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was once the Minister for Environment and Water, back in 2007.

Regarded as the worst leader in the nation’s history, as part of his machinations in seizing power in 2015 Turnbull hived off the water portfolio from environment and appointed National Leaders Barnaby Joyce as Water Minister.

He must have known full well the consequences for the country’s ravaged interior of handing control of the river system to someone so closely linked to the cotton industry.

Although he has now been pushed out of the top job, Turnbull’s fingers trail through the current catastrophe.

As Professor John Quiggin put it in a piece titled The Darling River fish kill is what comes from ignoring decades of science:

A multitude of actions Joyce took as minister, from blocking water buybacks to cutting the allocation of water to the environment were so damaging as to seem deliberately designed to destroy the fragile ecosystems of the Murray-Darling Basin, and to produce outcomes like those we see today.

Jack Waterford speaks for many critics when he argues the current catastrophe also owes much to the over allocation of water to irrigation farmers and to rorting of the whole system, with the connivance of public service regulators.

The fish don’t need a detailed inquest: just by themselves, they show that something has gone very badly wrong.

That federal ministers and some public servants in the primary industry department see their function as facilitating agriculture and maximizing its export revenue has also led to the corruption of the public stewardship they were supposed to deliver to the whole community.

Indigenous Heartbreak

The Australian media is heavily manipulated. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation is government owned and works as a kind of propaganda wing for the bureaucracy, while News Limited, owned by media mogul Rupert Murdoch, is closely aligned with and a champion of the conservative politicians now facing demolition at the polls.

While the collapse of Australia’s inland river system should be of interest to everybody, Guardian Australia has been one of the only news outlet devoting significant resources to the story.

For the graziers who built their properties over generations only to see them destroyed by the cotton industry and political bankruptcy, the situation is profoundly heartbreaking.

For the indigenous, who can date their linkages to the country back thousands of years, the death of the river system is emotionally and culturally devastating.

One recent Guardian Australia piece records:

Two rivers meet outside Walgett in north-west New South Wales: the Barwon and the Namoi. They are major tributaries in the Murray Darling system.

But they’re both empty, and this has never happened before.

Gamilaraay and Yuwalaraay elders who have lived on these rivers all their lives cry when they say they have never seen it as bad as this, and they doubt it can ever be recovered.

“This to me is the ultimate destruction of our culture,” Gamilaraay elder Virginia Robinson says, sitting with the Dhariwaa elders group in Walgett.

All people think about now is there’s no water. Aboriginal people were very close to nature and that’s all unbalanced now. There’s no nature to go back to.

We’ve got no water, no special places to go, no animals to hunt. Our totem animals are dead, their bones are everywhere.

When your totem animals are gone — the bandarr [kangaroo], the dhinawan [emu] — who are you as a person?

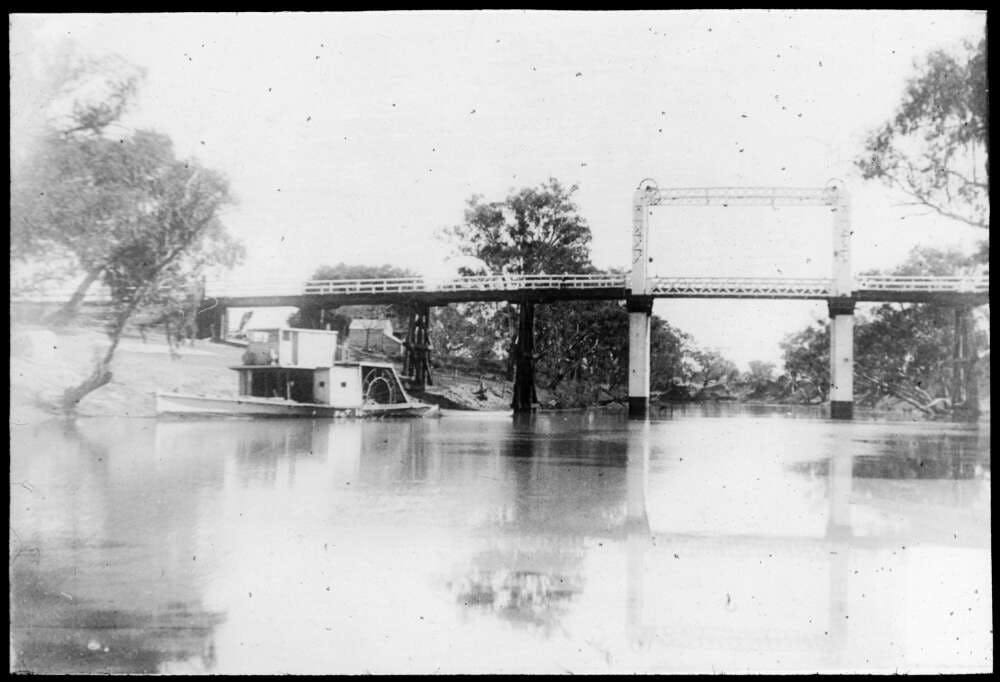

Wilcannia in western New South Wales was once the country’s third largest inland port.

Not any more.

Now the river is a tragic series of toxic water holes.

The Barkindji people called the river Barka; and refer to themselves as The People of the River.

Barkindji elder Murray Butcher says hundreds of kilometres of a once permanent river are now bone dry as a result of mismanagement.

He has called on “all us river people all along our river to join forces to fight these big irrigators, government and water boards to do the right thing by our land and waters.”

He told the national broadcaster:

This river system is a very important river system for the whole of western New South Wales, not just economically but spiritually.

Our river is just about on the brink of dying.

We have cultures on this river that have been here for thousands and thousands of years, cultures that have been obliterated by government decisions and mismanagement.

Because of the decisions they are making, we are the people that are suffering.

Another elder, William ‘Badger’ Bates, told Guardian Australia:

We don’t need a lot of cotton. We need our water.

When they take the water from a Barkandji person, they take our blood. They’re killing us. It’s not just us Barkandji people who are feeling it. It’s the white people and other people too.

How can I teach culture when they’re taking our beloved Barka away? There’s nothing to teach if there’s no river. The river is everything. It’s my life, my culture. You take the water away from us; we’ve got nothing.

Health worker Annabelle King was part a healthcare access consultation with the local Indigenous people last year.

Initially we queried after hospital wait times, access to healthy food and hygiene.

It quickly it became evident that the river was central to the life, spirit and health and welfare for the community.

The destitute state of the river was heart-breaking. The river gives healthy fresh food, clean water, cultural exercise, it keeps the young people occupied and away from smoking and alcohol. The river was everything- the health of the community is the health of the river.

The Perfect Storm

It has been a perfect storm of corporate greed, political betrayal and astounding levels of government incompetence.

Billions of dollars have hemorrhaged from the public purse.

Fear of disease, including ameobic meningitus, is spreading.

Until now, politicians have escaped the censure they so richly deserve.

But Australia is in an election year.

Drought is gripping the country.

And the government has used the plight of farmers as a direct propaganda tool. The first act of Australia’s latest Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, was to fly to Queensland to announce various drought policies.

That is, he chose to use the plight of farmers for his own political gain; the same farmers who successive governments have afflicted with excessive regulation, crippling taxes, whose land they have allowed to be readily sold off to foreign interests. Successive governments have tolerated or facilitateted outlandish predatory banking practices which have destroyed thousands of enterprises.

And now, as the government faces a truly disenchanted electorate, the consequence of their incompetence is clear for all to see.

There have been numerous scathing reports. Yet more are due in the coming days.

Senior counsel assisting the South Australian Royal Commission into the Murray Darling and its administration, Richard Beasley, was blunt in his criticisms of the Murray Darling Basin Authority and its political masters scattered across the Federal, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australian and Victorian spheres.

Describing issues of “maladministration” and “unlawfulness” and “mismanagement of huge amounts of public funds”, Beasley sheeted home blame to those in charge.

While the Royal Commission report is expected to be released this Friday.

One such report, by the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists, found excessive payments to irrigators, failing environmental flows and an ignorance of water extraction that is “inconceivable” given available technology

Key author of the report Dr Jamie Pittock said:

It’s the capture of state agencies by the powerful industry interests against the broader public interest.

There was institutional corruption.

It’s appalling that the health of the red gum forests continues to decline, and it’s appalling the number of water birds has flatlined.

Greens water spokesman Jeremy Buckingham has been batting on about the state of the inland rivers for years, with little if any impact.

He has finally been vindicated.

We are on the brink of failure because of recalcitrant states, a tame Murray Darling Basin Authority, a dysfunction water market that is being rorted, a lack of compliance, and National Party water ministers acting to destroy it”.

We have had cascading reports concluding the Murray Darling Basin Plan is failing and billions of taxpayer’s dollars are being wasted on projects that are not restoring our rivers and wetlands.

Bill Johnson is scathing about the bureaucratic and political responses.

“We don’t know, we can’t find out, it’s not our job,” that’s the attitude.

Federal and State agencies have all been saying it’s not our fault.

It’s like the Bart Simpson defence: I didn’t do it. Nobody saw me. You can’t prove a thing.

There is no doubt governments have abandoned the river.

When you abandon the river, you abandon the people who live along it.