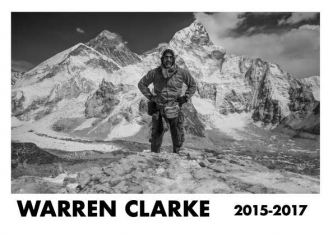

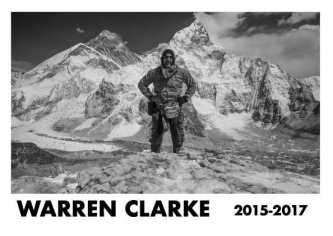

Warren Clarke was known for his high adventurism.

Whether on assignment or not, he trekked to places no other photographer wanted to go.

In recent years he had become fascinated by India; where he did some of his greatest work.

In November of 2017, unable to sleep, he was possessed with a strong impulse to return home to Australia.

He had a medical checkup, was diagnosed with three lesions on the brain, and was dead in just over two months.

It was a shocking end for

Warren Clarke was known for his high adventurism.

Whether on assignment or not, he trekked to places no other photographer wanted to go.

In recent years he had become fascinated by India; where he did some of his greatest work.

In November of 2017, unable to sleep, he was possessed with a strong impulse to return home to Australia.

He had a medical checkup, was diagnosed with three lesions on the brain, and was dead in just over two months.

It was a shocking end for someone who had always seemed so very much alive.

One of his last wishes was to leave a legacy for his children; which is when his friends Russell Shakespeare and Michael Amendolia promised him they would pull together a collection of his recent work.

The resulting book has been made available through Momento this week.

On news of his death tributes flowed in from around the world.

Admired photo-journalist David Dare Parker recalled: “It was almost 20 years ago when a small group of talented photographers, including Warren, welcomed me to Sydney with some drinks at a pub in Circular Quay.

“Wazza then helped get me some shifts at The Australian — and that helped a lot. Generous to a fault and great company. RIP mate.”

But there were many other tributes.

Amendolia recalls:

“He was a consummate traveler.

“He would travel for years on end with his mates, living in a simple way, long before he picked up a camera.

“His life became a mixture of struggle and meeting his dream. The photography gave meaning to his travels, the people he met, the experiences and opportunities he had.”

Warren Clarke grew up in rural Queensland, Australia. His father was a builder. Nothing was handed to the family.

That modesty, a hard working background, was very Australian.

Unlike today, when everybody is shouting every one of their minor accomplishment from the rooftops, boasting of personal achievements just wasn’t done.

As a young man he was an accomplished horseman, for example, winning a number of competitions, but in later life never bothered to tell anyone. Most people didn’t know, until the stories emerged at his funeral.

He was one of those people who applied himself to anything he wanted to achieve.

He was what Australians call “a rough diamond”.

But a complex person.

He began his career as a photojournalist in London in 1989, working for an East London newspaper.

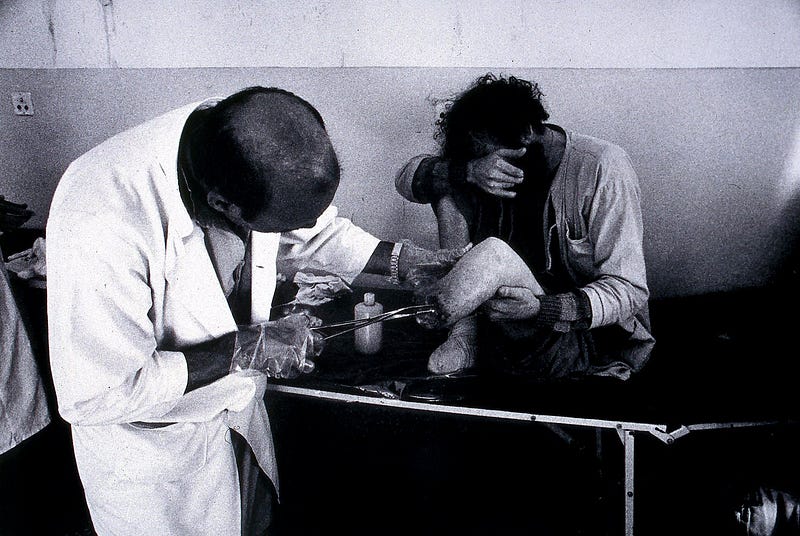

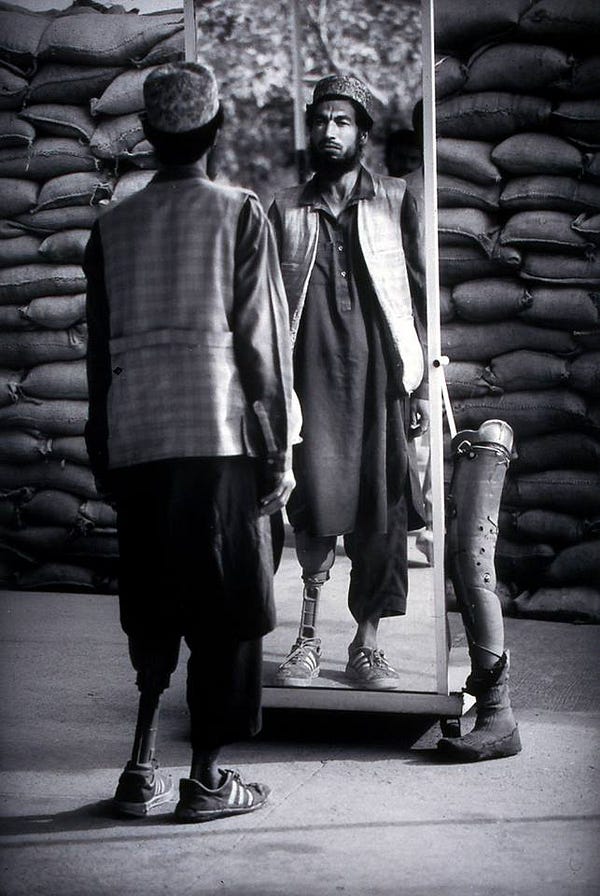

He covered assignments in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and the South Pacific, and for three years documented the repercussions of land mines around the world.

Warren’s work has been published in The New York Times, Newsweek, The London Sunday Times, The Australian, and by news agencies Reuters and the Associated Press.

He won the United Nations Human Rights and Austcare awards for excellence in photojournalism.

He could be a bit of a rough head, but when his children came over to stay, he would fold the bed sheets and blankets as if he was working in a five star hotel.

He would befriend anybody who was genuine and decent. But more than anything he wouldn’t suffer pretentiousness.

He was the sort of guy who, if he had to, could throw you over his shoulder and walk five kilometres while drinking a long neck of beer.

He was that sort of strong, durable guy.

Land Mines

Michael Amendolia recalls: “Warren did beautiful travel work.

“But the sort of work that was journalistically significant was his work on land mines when he went to three different countries, Angola, Cambodia and Afghanistan.

“He funded many of the trips himself, but would work with the Red Cross and other organisations on the ground.

“I believe his best work was done in Afghanistan.”

The experience really shook him up.

As it would shake up anybody.

But Warren had the courage not just to look, but not to turn away.

His work on landmines was widely exhibited, with the help of the Red Cross and Medecins sans Frontieres.

Exhibitions included The Legacy of Landmines held at the Sydney Opera House.

Warren was in Afghanistan during the war, and traveled to the front line.

But he ran into one of history’s greatest war photographers, James Nachtwey, who told him that he should skip the front line and concentrate on the consequences of war, because that was where he would get his best pictures.

If Warren had a hero, an inspiration, it would be James Nachtwey. And he ran into him.

James recognized him as a fellow photographer at a gathering of NGOs working in Kabul, came up to him and they started talking.

Warren was an enormous admirer of Nachtwey and had all his books.

As Nachtwey says of his own work:

"I have been a witness, and these pictures are my testimony. The events I have recorded should not be forgotten and must not be repeated."

The first time Warren traveled to Afghanistan, he went to visit a medical centre.

A doctor threw a body part at him to catch and said: “Welcome to Afghanistan.”

Warren the Wanderer

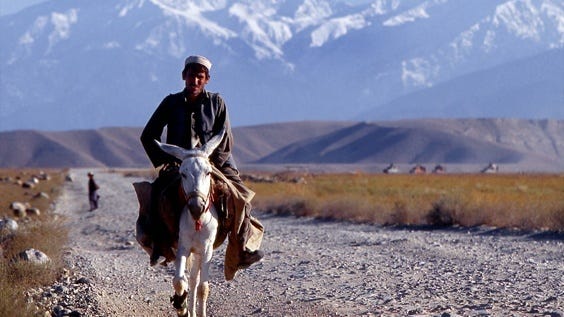

Warren was an inveterate traveler.

He went to Burma when nobody went to Burma. When the regime was hostile to foreigners. He saw places that almost no other Westerners had seen in decades.

Now Myanmar is a major “go-to” tourist destination. Warren saw it when it was at its most spectacular and untouched.

Back then, Warren would just turn up on his own and hire a local driver, who drove him around in one of those classic old Ambassadors.

A lot of people wouldn’t travel there because they didn’t want to support the regime; but that didn’t stop Warren.

He went to Iran when everybody was being advised not to travel there.

He went to base camp on Mount Everest in the middle of winter without a guide. He got stuck in a blizzard, and if it wasn’t for the locals he could have frozen to death.

In India, he would travel the cheapest way possible. If there was a third class ticket, he would buy it. If there was a tractor, he would hitch a ride. That was the way he would travel. Everywhere.

Every year he would try and find somewhere that he was interested in travelling to.

He would get bored with news and corporate work, and just wanted to get away.

He would rarely spend more than $20 a night on accommodation. Mostly less.

One year it would be South America, another year Africa, somewhere that he hadn’t been to before, or that he wanted to revisit. One year Cuba.

He loved Bali in Indonesia long before it became the destination for millions.

Amendolia recalls that it was a combination of travel and photography that motivated Warren.

“He was an inveterate wanderer ever since he was a young man. I think he first left at 16 or 17 when he headed off to Bali for his first trip overseas with his great mates.

“And they would go travelling round the world, to the most remote parts of Africa. There was a bit of ratbaggery about it all.

“It never really left him, this wanderer, traveler side of him. He enjoyed the process of discovering a new place. He was interested in the culture, the process, finding somewhere new to eat, sleep.

“He wasn’t just going somewhere for the sake of a story. Part of it was the wanderer in him.

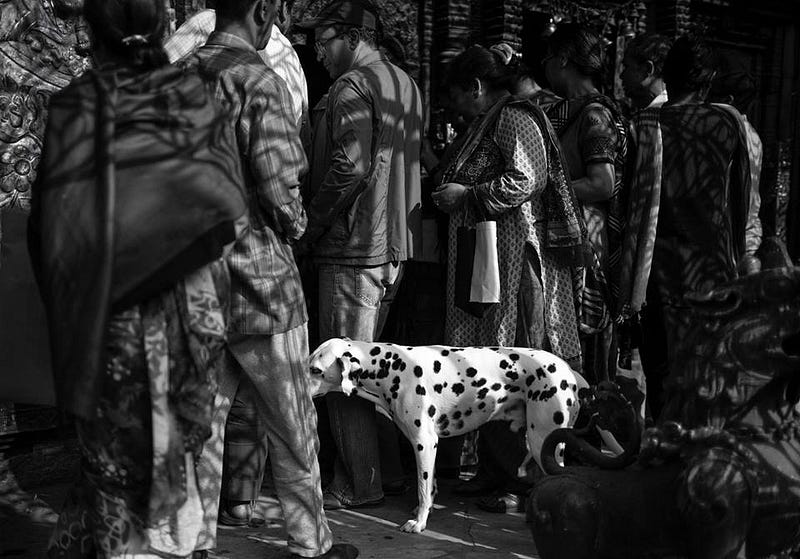

“Delving through his archives, you get the strong sense he was the classic street photographer.

“They don’t have anyone organizing anything. They don’t have a fixer. They just discover the country as it presents itself.”

He particularly loved Amed, which is a beach resort sheltering under a volcano. He could have retired there. He would travel there at least once a year, and had done so at least once a year for 20 years.

When you talked to him, he was always planning his next trip.

He would always ensure he could break away to travel somewhere.

And inadvertently he would take pictures.

Sometimes he would get a travel magazine to publish before he went, or when he got back to Australia.

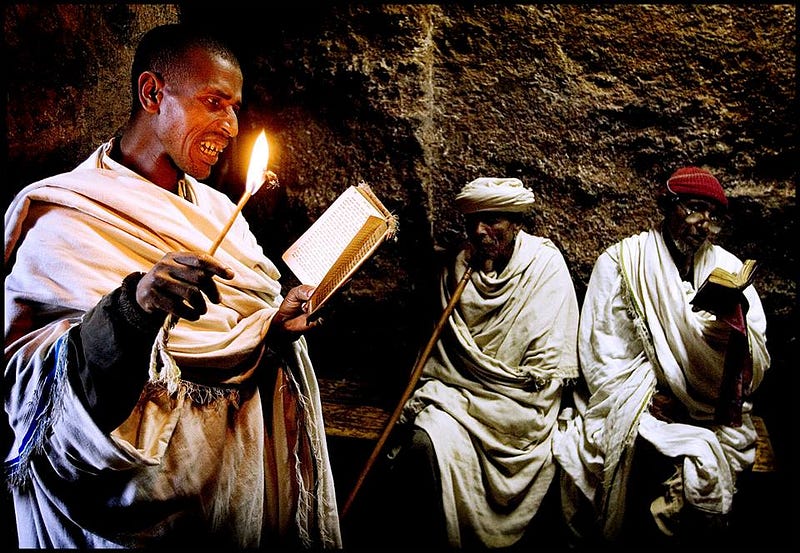

He would go to places just for the sake of travel, he wanted to go to Ethiopia, to a part where there is a big festival for Orthodox Christians.

He could fill all his aspirations by traveling; photography, meeting people, a desire for adventure and intensity of experience.

And Warren did it all before the world became one giant theme park, filled with idiot complaining tourists with absolutely no idea of what they are looking at, cooing about hotels and airlines and restaurants.

That wasn’t Warren for a second.

Warren In India: The Final Years

In 2016 Russell Shakespeare was traveling to India with his friend and former picture editor at The Australian newspaper Marco del Grande.

Marco was also Warren’s picture editor some twenty years before, so they knew each other well.

Warren was on the second year of this three year odyssey and we agreed to meet in Varanasi, India.

Russell recalls: Within five minutes of arriving Warren said mate, would you like a cup of coffee. He had his own coffee machine he was travelling with.

That was Warren all over. Simple but hospitable. He knew we had taken a long journey.

He was staying in the room I normally stayed in. It was cheap, but it had the best views overlooking the Ganges River.

Warren was just wearing thongs. Not many people are brave enough to just wear thongs on the streets of India, let me tell you. Not with cows and dogs and the general obstacles you need to avoid when walking the streets of India.

There was me, Marco and Warren, and we wouldn’t want to be shooting the same thing. So we would agree to meet at the chai shop at 8am each morning, and sit and talk about what we had been photographing. And make a bit of a plan for the day.

Warren was the master of living on nothing, so we decided to see if we could live on three meals a day for under five dollars.

We would just eat at the local food places. Nowhere fancy, just the local guys cooking on the streets.

The picture below is of Lali Lali. We don’t know if it was because he had been on the road for so long and was missing his own children, but he was very good with kids.

This girl connected with Warren, and if he was at the chai shop, he would always buy her an extra chai and a bit of food.

I don’t know the full reasons why he wanted to do a three year odyssey in India.

From what I understand, he just wanted to live the free life for a few years, and do a meaningful, significant body of work. He wasn’t sure what the outcome would be, but he wanted to travel India from the bottom to the top.

Warren always talked about doing a book and an exhibition at the end of the odyssey, although neither had been formulated in his head at that stage.

The other thing I found intriguing about Warren is that he seemed to have no fear of anything.

Talking to friends of his at the funeral, he had been held up at gun point at various times, and they had all been shaking in fear, but he hadn’t been flustered at all. He had a kind of faith in humanity.

He was missing his children and wondering how on Earth he was going to fit back into a normal life in the suburbs, getting up and going to work for a newspaper or a magazine, all over again.

The last message Russell received was:

“Anyway mate, I’ll be back at Christmas, and I’ll show you all this unseen work.”

That’s how it all came about, that we have put together this Momento book as a tribute to him.

So much of his life was unfinished.

He was amazingly calm about his destiny, but it wasn’t his time to go.

Warren had a wonderful gift for life, for travel, for enjoyment.

And he was a wonderfully talented photographer.

Spirited to the End

Warren made friends wherever he went, even in his final days.

Varanasi Photographer Anand Singh was keen to do a Puja for him, a Hindu ritual of reverence, beside the eternal river, the Ganges at Varanasi, where he first met Warren.

Anand’s nickname for Warren was “travelling baba”, which is a reference to the Hindu holy men, the Sadhus, who travel penniless across India as part of a sacred rite.

When I told him Warren had died, I was hoping for a very Indian, philosophical response. Instead, Anand broke down and cried. In all my conversations with Anand, about living and dying, he was very Indian. Life is life and death is death. I thought he was going to give me some great Indian wisdom.

Instead he just broke down and cried. Which shows how much love and respect Warren was held in.

We went up to Brisbane to have dinner with Warren and start going through the editing process for his book.

We cooked some Indian curry and had some beers.

Warren was in good spirits.

The next morning Michael, Warren and Russell Shakespeare did a nine kilometer walk. He wasn’t panting or struggling.

Russell said: “Mate the way you’re looking, you could come to India with me. He actually looked really well.

“But it wasn’t to be.”

Michael: “When he told me he only had 12 months to live I was, of course, shocked, horrified and saddened.

“I was up there for some Award thing, and I came to visit him at his parent’s house.

“We started looking through the photographs for what was to be his Indian book.

“We thought that was something useful we could do in the year we thought was available to us, something he could leave for his family.

“He would have loved to have come down to Sydney to see all his friends, but he was too unwell. He had to keep going back and forth to the hospital for medication to stop the seizures.

“He didn’t want us to feel sadness for him. While we were with him, he just wanted things to be as they used to be, regardless.

“He was talking a lot about his children. He wanted to make sure he left something for them.

“We had a bowl of noodles together and talked at length. It was all very philosophical. We kept it the way he wanted it to be. Not sad.

“He had seen a lot of life in all its layers. It’s another matter when the worst thing happens to you. But I got a lot of personal inspiration the way he was handling, for the sake of everybody else, this predicament he had.

“He wanted us to celebrate his life not dwell on the cards he had been dealt at the end.

“Even in those last three years, he lived the life of ten men.”

People all over the world knew Warren. Tributes flowed from everywhere.

Some of the tributes were in broken English. He had friends everywhere.

Photographers Russell Shakespeare and Michael Amendolia have sifted through thousands of images to compile a collection of his recent work.

No comments:

Post a Comment