Yen’s White Lie details a complicated lover’s tryst in Old Saigon. But the city itself is as much of a character as the denizens that haunt the atmospheric alleyways and cafes of the past.

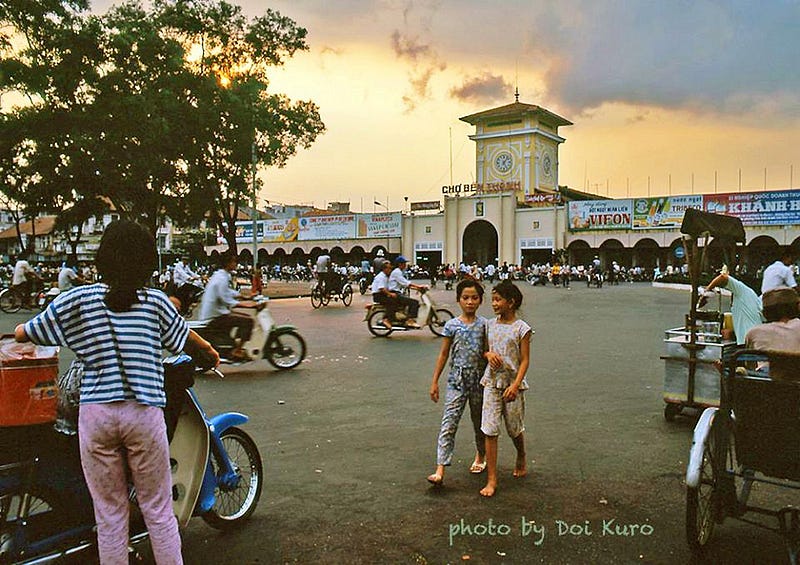

When author Charles Gerard first came to live in Saigon in the mid-1990s, the former capital of South Vietnam was in many ways little changed from the atmospheric days of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, to this day the most famous book set in the city.

The fierce, brutalising poverty that took over the nation following the American War, as the Vietnamese call it, was still everywhere evident.

Not anymore.

Even more striking than the enigmatic character of Yen is the city of Old Saigon, a city which is now changing dramatically every day as money flows in from across Asia, a new crossroads of modernity and ancient custom.

New skyscrapers and housing estates are emerging from the urban sprawl and semi-rural areas daily. Expensive cars and impressive mansions signify the rapid expansion of the Middle Class and a crossroads city becoming a fundamental part of the 21st Century Asian boom.

Saigon is a city full of romance, intrigue, and to this day expatriates are drawn to the city’s many mysteries.

To an inexperienced eye, one of the most striking things about Yen’s White Lie is the portrayal of the colourful cast of characters making up the expat community; as if a direct line can be drawn from those drunken old soldiers and assorted miscreants to the denizens of today.

But to Charles Gerard there are many obvious differences.

The scene at the Old Saigon Cafe, a central part of Yen’s White Lie, has moved up a block.

“The difference between expats back then and expats now is that people were a lot more adventurous back then,” Gerard recalls. “In the 1990s this place had just opened up. Everything was a challenge back then. There weren’t as many opportunities, so you had to be resourceful.

“Now I see a lot of young kids fresh out of college who just think this is a cool place to go.

“It is easier and cheaper to come here now as a Westerner, so we get a lot of tourists. Before it was Bali. Now it is Saigon. We get a lot of those tourists these days. They come here to party, mostly with each other.

“When I first arrived, there were no neon lights. Only the Saigon Cafe stayed open after 11pm. Everything was shut. Now you can party 24/7.

“There were only a few English teachers here and I knew all of them basically. There was no internet, no email. It was very different back then. Adventurous. When I look at old photos back from the 1960s, it wasn’t very different in 1997.

“There were no highrises. The tallest building was The New World Hotel, which is near where I now live.

“You could see it form the airport. Now it is entirely dwarfed by the buildings surrounding it.”

According to government statistics there are approximately 85,000 expats living in Vietnam, and studies show they are amongst the happiest expats in the world.

“The streets were a lot narrower and sometimes when I got lost I would just look at the New World Hotel and knew where to go.

“What we see today is a lot of expats sitting in cafes drinking every day.

“People were heavy drinkers back then but I wouldn’t say they were drunk everyday. These days people drink a lot more.”

Gerard says many of the expats he knew back in the 1990s went on to marry Vietnamese women and have children, many of whom are now in college.

“Some moved back to the States. Some are still here. Some divorced.

Then, as now, one of the major subjects of repeated hilarity at bars and cafes frequented by expats are their sexual adventures with local women.

It is a subject captured neatly in Yen’s White Lie, where a couple of the “Only in Asia” scenes leave little to the imagination and are, yes, completely hilarious.

Western men in Asia often have a poor public image, as drunken predators preying on poor, vulnerable women, using their money as a vehicle of exploitation.

“I sometimes feel it’s the opposite. As in, who’s exploiting who? It is not clearcut.

“There are plenty of foreigners who marry Vietnamese. Some marriages work out, some don’t.

There are, of course, two sides to every story. Or in the case of Yen’s White Lie, three sides.

“I used to teach these mail order brides English; and I would talk to some of their fiances.

“Some of these girls were using these guys as tickets out of the country. Sometimes I talk to these girls years later, when they came back, and they tell me they had a horrible time in the West. That they were basically trophies. ‘Look what I got from Vietnam.’

“These girls find it hard to assimilate, they have a lot of trouble understanding our culture. In the West it seems to me everything is black and white, good and evil. The longer I stay in Asia the more it feels that life is shades of grey. You can’t really assume anything. It is just so different here. Nowadays I don’t always inquire too closely.

“My book is a collection of anecdotes embedded in a work of fiction. A lot of the scenes are stories from real life. I may have changed the setting; it didn’t happen in this district or street, to make everything fit, but a lot of these things did happen. I wanted everything to be as realistic as possible.

“Yen is a fictional character, but a very realistic fictional character based on a real person.

“You could walk into her in any of the alleys around District One, particularly the entertainment district around the infamous Bui Vien.”

Gerard says he has specifically not identified the nationality of the principal protagonist, Randy.

“Randy is an expat, but he could be from anywhere. Even today in Saigon you can sit at a table of twelve expats and every last one of them is from a different country.

“Randy is like the average “round eye” you would find at one of these tables.”

Many expats still find favourable exchange rates and the relative cheapness of Vietnam, along with the eternally fascinating excoticness of a place entirely unlike the West. But for people like Charles Gerard, there is an inevitable nostalgia for the past.

Which is exactly how Yen’s White Lie came into existence.

“I was talking to an old friend about the good old days, and I was saying I don’t even have any old photographs. I told him I write things down. When you read it again, it brings back memories. There were certain things I didn’t want to forget. I started writing down these anecdotes. My friend said, you should write a book.

Yen’s White Lie divides into two halves.

“I wanted it to be from two different perspectives, from a Westerner’s point of view and a Vietnamese woman’s point of view.

“I find this culture fascinating. Sometimes I try to imagine what it is like, being from this place. I’m not from Vietnam, obviously, so I look at this country in a very different way.

“Their perspective, how they look at this city and how they look at us, that fascinates me.”

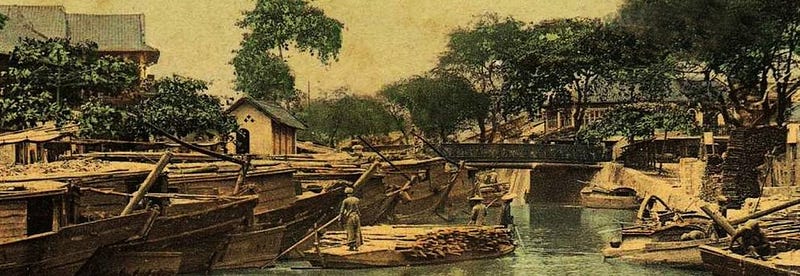

There is a phenomenon known as euphoric recall; humans tend to remember the high points and forget the lows. But even as it transforms into one of the world’s great cities, it is the romance drenched past which will perhaps forever remain one of Saigon’s most compelling images.

“People used to sit on small plastic chairs on the sidewalk, enjoying a 3000-dong cup of strong coffee,” recalls Gerard. “Now it’s popular with young Vietnamese people to sit in a Starbucks-like cafe with friends and sip 40,000-dong iced coffee.

“Vietnam is one of the world’s fastest economies, which is good for them, but for a lot of expats it seems to be spiraling down. Our wages haven’t gone up, but the cost of living has gone up dramatically. My rent has gone up 300%, but my daily wage hasn’t gone up anything like that.

“Things are changing so quickly. And will change again. I hope Yen’s White Lie adds a little to an understanding of the past, before it is overwhelmed by the future.”

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS:

No comments:

Post a Comment