Bridget Lafferty Leaves Redfern: The Best Of.

Images, paintings and recollections by Bridget Lafferty

Editors Note: This story, written way back in 2018, was pivotal in the evolution of A Sense of Place Magazine, because it was at this very point that we realised and came to understand the potential of the new publishing technologies.

Bridget Lafferty was an old neighbour of mine in Redfern, an inner-city suburb of Sydney, Australia, full of what are sometimes colloquially known as “cutters”, or characters.

I was an aging journalist of occasionally ill repute.

Fast track back ten years and this story would never have been published. I would never have been able to convince a Features Editor that Bridget Laffety was of enough cultural import to festoon their pages. And even if I had managed to finesse it past them, the project would have involved a photographer, a picture editor, a page designer, a sub-editor, not to mention that the sections editor would then have to convince his boss that this was a story which really should be run this week, rather than spiked on the never never.

There was no compelling financial or strategic reason to do this story. There were no press releases, no corporate interests.

I just happened to know that Bridget was moving on and she had done some paintings of the area.

We were both, perhaps, somewhat of a loss one afternoon back then, and we bashed out this story between us in an afternoon, perched between packing boxes. It took a little more than four hours, and I pressed the “Publish” button shortly thereafter; for a project which would have once involved multiple personnel and taken days if not weeks to execute.

So many of our lives pass unwritten. Some have the courage to leave a record. Editor John Stapleton.

People dwell in large cities for different periods of time, for different reasons.

Then they disappear. Without a record, they disappear even more finally.

Bridget Lafferty, artist and high school teacher, came to Redfern in 1999, looking for work, love and life.

My initial reaction was shock.

That was the final years of the heroin epidemic which had turned Redfern place upside down. The place was wild. Truly wild.

A police crackdown in other parts of Sydney had driven dealers and addicts to the narrow streets of Redfern, which were essentially lawless.

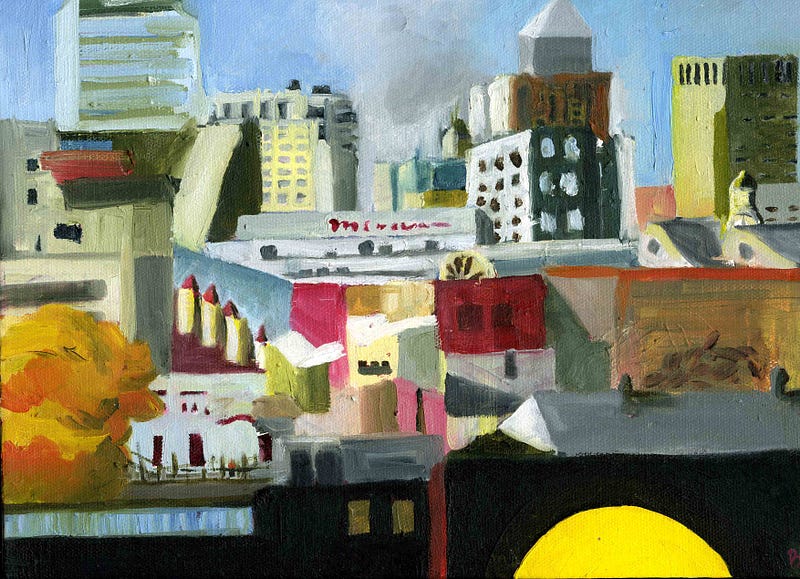

Bridget painted many images of the area, including this one.

I love the squares. I wanted to capture the way the buildings catch the facets of light and create a pattern.

There are many whimsical and historical elements to this area, but this painting was really only about a play of light.

The Aboriginal flag gets in there, and tells me there is a new sun rising.

The city of Sydney is usually depicted as a sparkling harbour with the Bridge and the Opera House.

This is the dirtier side, looking from the west, and is the rougher view.

That’s the way I see the city, with the Aboriginal flag at the centre, rather than the Harbour Bridge.

And the city has turned its back on us.

That’s what I feel.

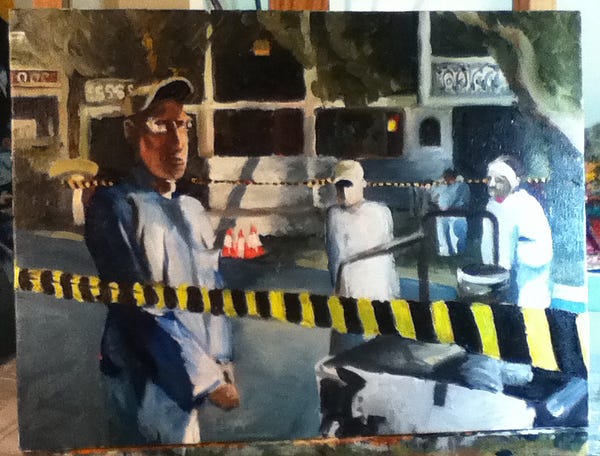

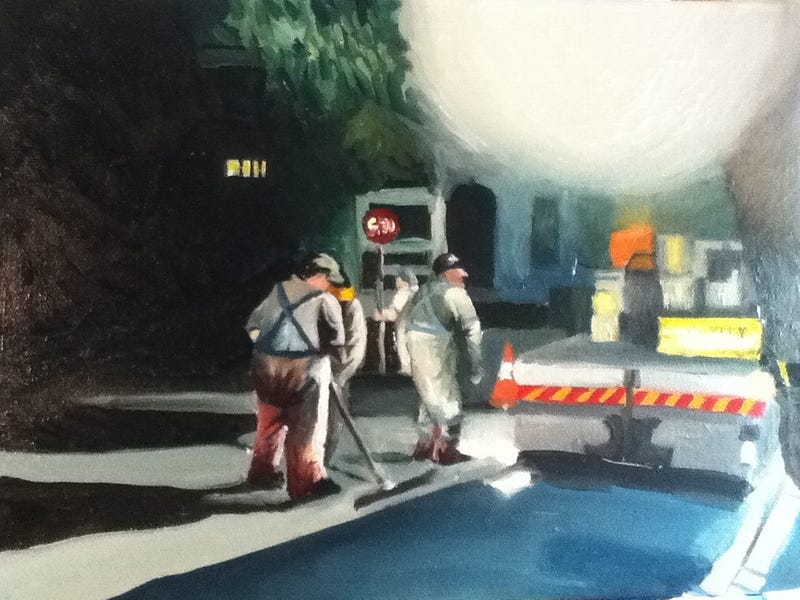

I see my students as artists, I wonder if their parents are road workers

We stomp all over them.

Drive our cars all over their work.

The whites treat them like dirt. Definitely. But they’re the workers, they’re the ones who are doing all the hard work at night making everything beautiful for us. Their so much more than what the world sees them as.

Then we come out during the day.

And don’t appreciate all the work they do for us.

But they are the ones who keep the city going.

The Glengarry Castle

Much of Redfern’s social life revolves around the local pub, the infamous Glengarry Castle.

“I met my then partner there, Mick O’Brien.

He was an SBS news cameraman. I was pretty impressed by that.

He was also a musician and was singing and playing beautifully with his mate Phil Cole when I first saw him.

And of course he was Irish.

Mick was pretty much the love of my life but that’s the saddest thing in the world because we only went out for two years. If anyone’s my husband it’s him. We’ve been friends in the ten years since we broke up.”

I was sick of going out with the girlfriends to dinner talking about stuff. I didn’t know any stuff. I felt like I was poorly educated.

I don’t need to pretend that it’s a better way to be, knowing stuff.

So that’s why I loved the Glengarry, hanging out with all the other people who didn’t know any stuff either, but certainly knew how to play music, and how to drink.

Mick was the same. When he went out with all his colleagues he was dumbfounded, barely said a word.

But at the Glengarry he was King.

When we’re not good with words, we use pictures and when we’re not good with pictures we use fists. That’s the way we are.

The Local IGA

I like the way the trees bend. It reminds me a little of Cezanne.

I was influenced by what I was teaching my students, Mr Lathuris’s unit on the Fauves, a group of French painters, the best known being Matisse.

That section of Regent Street is actually rather bleak, down near the housing estates.

The painting is really pretty; but it’s a dirty part of the world.

I would never go to the doctors down there. It was Junky Central.

I don’t feel comfortable in this world, so sometimes I would go down there to shop.

IGA stands for Independent Grocers of Australia.

I was working from intuition, and that was what came out.

I don’t really know why I painted this painting.

I liked the wiggly trees. They are trying to find the light.

I was just looking for images.

I was feeling really empty and lost. And also not wanting to be so subjective. Self expression was no longer something urgent, I had stopped exploring my inner self and started observing with my image making; it was a stage of growing up. Being less subjective, more objective.

Just looking at the world around me, and being lost in it.

Gersch

The crush. Alright, it was a good old fashioned, fateful crush.

Tug of the heart. We all laugh.

Gersch.

Immigrant Jewish background.

Nouveau rich but working class.

Gersch was a builder and a drummer, fine at both.

His parents wanted him to be a builder. He wanted to be a drummer. In the end he excelled at both.

And went kind of mad, for awhile.

His masterpiece is his house. The house in this painting.

It might look ordinary on the outside.

Inside, it an in progress architectural work of genius, all made by his own hand.

His is the same story as others I am drawn to; everyone with a troubled background, the parents are workaholics, my father was a workaholic, emotionally disturbed.

They’re really beautiful, artistic, work their asses off, these people. They’re just not part of the established elite.

That was Gersch.

Subjective to the Objective

When you’re young you wonder around the world trying to figure out who you are.

In our youth we protest, we scream and cry.

It wasn’t until I was 35 before I could look at the world I was in.

It took that long for me to grow up and stop crying and lamenting and open my eyes and see.

That doesn’t mean it’s a higher form of art, in fact lesser because, I have less to say.

I have conformed; they have tamed this shrew.

That is why I want to go back to being less fluffy, more convinced, more determined.

Fuck the art world.

The grownup world. I don’t want to be in that world.

You have to be able to cry and lament, but if that consumes everything, you’re a junky in a housing estate. Autism, dyslexia, they are all emotional disturbances.

White middle class people do well because they have less troubles.

I don’t want to paint landscapes anymore, I don’t want to be objective, I want to be subjective.

I want to go back.

John Stapleton was one of Bridget Lafferty’s neighbours for more than eight years. During this time he was living with his then young children and working on The Australian newspaper.

A collection of his journalism can be found here.

Bridget Lafferty works as a high school arts teacher and also paints. She lived in inner-city Redfern in Sydney from 1999-2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment