Murder On Lower Fort Street: Best of the Archives

With Photography by Tim Ritchie

There is no more historic, more superbly located or visually rich part of Sydney than The Rocks.

Tucked in under the southern flank of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, from the earliest days of the colony it was known as a slum, for its gambling dens, drinking houses, lively women, dirt poor housing.

Just around the corner from the multi-million dollar selling homes on Lower Fort, with unfettered views to the harbour, is where the first bubonic plague victim died, on the 19th of January, 1900.

He was Arthur Paine, a 33 year old delivery man whose daily work brought him into contact with Central Wharf.

A few short steps away, on the former site of the Live and Let Live Hotel, the Stevens Buildings 1900. With its four floors and 32 rooms, it was the first walk-up block of flats in Sydney.

Some of the surrounding sandstone block buildings date back to the 1840s. Throughout the 19th Century the area was known for gambling dens and brothels.

The period beginning in 2010 now sees the area in its final throes of becoming a wealthy enclave.

But in this place, where the mewling masses once made a living on The Fatal Shore, a modern day real estate rush, government connivance, wiping clean the history of an underclass is a story where a ledger is not held, and history dogs every step.

With the best views in Sydney as a backdrop.

The Meaning of Life: A View is Everything

No one in Sydney, wrote playwright David Williamson in his love hate paen The Emerald City, “ever wastes time debating the meaning of life — it’s getting yourself a water frontage”.

Guess who just sold it. Guess who just bought it.

As the state’s Community Services Minister, Pru Goward announced in mid-March 2014 that around 300 harbourfront public housing properties would be sold under the management of Government Property NSW.

Some sixty properties already lay vacant.

The remaining public housing population would be relocated

The state government generated hundreds of millions of dollars from the sales.

Pru Goward justified the sale:

“In the last two years alone, nearly $7 million has been spent maintaining this small number of properties. That money could have been better spent on building more social housing, or investing in the maintenance of public housing properties across the state.”

The NSW government could have adopted a civilised approach.

Instead the NSW Planning and Housing Departments managed to alienate everybody, the tenants, the media, the housing workers themselves, and the police who had to deal with the consequences of political and administrative ineptitude.

With just a modicum of decency and common sense the protests, the waving banners, squatters, distress of the residents, premature deaths and hostile media coverage the state government generated could all have been avoided.

It is hard to imagine a bigger debacle at Millers Point if you had been planning it from birth.

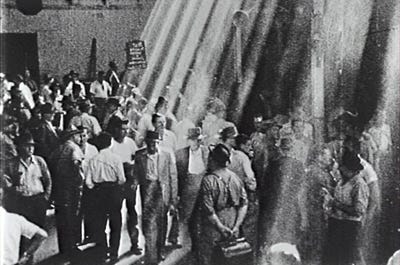

The Hungry Mile

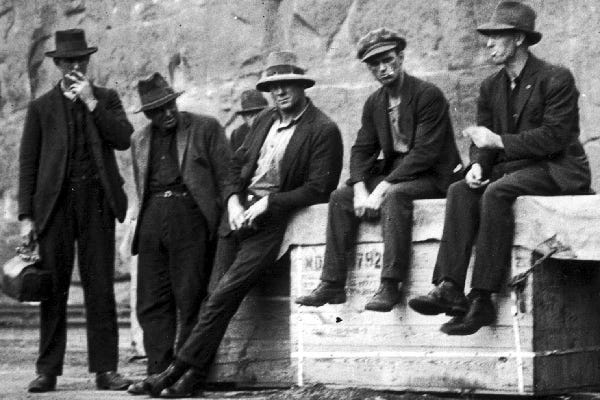

The battles echoed a harsher history.

During the Great Depression the docklands were called The Hungry Mile by harbourside workers searching, often fruitlessly, for a job.

They tramp there in their legions on the mornings dark and cold

To beg the right to slave for bread from Sydney’s lords of gold;

They toil and sweat in slavery, ‘twould make the devil smile,

To see the Sydney wharfies tramping down the hungry mile.

On ships from all the seas they toil, that others of their kind,

May never know the pinch of want nor feel the misery blind;

That makes the live, of men a hell in those conditions vile;

That are the hopeless lot of those who tramp the hungry mile.

The slaves of men who know no thought of anything but gain,

Who wring their brutal profits from the blood and sweat and pain

Of all the disinherited that slave and starve the while,

Upon the ships beside the wharves along the hungry mile.

But every stroke of that grim lash that sears the souls of men

With interest due from years gone by, shall be paid back again

To those who drive these wretched slaves to build the golden pile,

And blood shall blot the memory out — of Sydney’s hungry mile.

The day will come, aye, come it must, when these same slaves shall rise,

And through the revolution’s smoke, ascending to the skies,

The master’s, face shall show the fear he hides, behind his smile,

Of these his slaves, who on that day shall storm the hungry mile.

And when the world grows wiser and all men at last are free,

When none shall feel the hunger nor tramp in misery

To beg the right to slave for bread, the children then may smile.

At those strange tales they tell of what was once the hungry mile.

Ernest Antony (1894–1960). The Hungry Mile.

The Visitation: State Generated Chaos

The NSW Government needlessly provoked years of protest at Millers Point, costing the state’s very long suffering taxpayers millions of dollars.

One observer, Praba Balasubramaniam recalls: “About 70 to 80 people took part, some going inside the block others keeping watch outside: trade unionists, former Millers Point public housing tenants, public housing tenants from other parts of Sydney, people renting privately and paying too much rent because there is not enough public housing and other supporters of public housing.

“The public action lasted about 5 hours until riot police went in with heavy force.

“The occupation was a rear-guard action to stop the sell-off of public housing in the Millers Point, Rocks and Dawes Point area. Sadly, all but a handful of public housing tenants who once lived in the area have now been squeezed out as part of the state government’s plan to sell off nearly all the public housing in the area.”

One scene the author personally observed occurred in mid-September of 2014, in a scene repeated a number of times across the historic suburb, it took 12 policemen and several housing officers to remove squatters from one of the houses on Argyle Place in the centre of The Rocks.

Posters and banners on surrounding houses sent the message:

“Save Our Community”, “Save Our Heritage”, “Save Our Homes”, “Living Community History Not 4 Sale.”

There were also blown up posters of newspaper articles:

“The state government is offloading 100s of harbourside homes at Millers Point without economic modelling or an up-to-date social housing plan, raising doubts over the integrity of the controversial sale.” Sydney Morning Herald.

As the squatters briefly stood their ground in Argyle Place, a band of protestors and other interested parties watched silently or heckled the police, who were just doing their jobs and should never have been placed in the situation they were; and the housing officers, many of whom don’t agree with what they are being asked to do.

After a standoff lasting several hours the students drove off in a late-model Rav-4.

In truth they weren’t the genuinely homeless. They were just protesting the bully tactics the NSW State Government used to rid the Rocks of public housing tenants; and to sell-off some of the most spectacular real estate in Australia.

Fast forward to 2017, and there were barely a dozen residents left, with an estimated 500 moved from the area.

The forcible removal of activist hold-out, 57-year-old Peter Muller, sparked days of protest.

A spokesperson for the residents, Barney Gardner, told the protest:

“After an all-day picket outside Peter’s home yesterday, police forced their way in this morning, escorted the young people out and put Peter’s belongings in a removalist van.

“The government and department have told lies all through this process. We have suffered three years of stress, including suicides and multiple hospitalisations of elderly and vulnerable residents.”

Eradicating Memories

There was a flurry of media stories emphasising the attachment inhabitants had to the area.

The large number of tenants with historical links to the area was due to the fact that many of the houses were originally rented from the Maritime Services Board, prior to the properties being handed over to the Housing Department decades before.

“My father was a waterfront worker.”

“I can remember as a child in the wool season, the big horses with the bales of wool.”

“The row of terrace houses that I live in now, it is supposed to be the first row of terrace houses in the country, we moved in here in 1946”.

Amidst all the banners and posters, photocopied, A-4 sized photographs of elderly residents have been placed in strategic locations around Millers Point, each of them accompanied by stories from their lives:

“Everyone had their hotel, but no one used to be exclusive because they knew their mates would be at a different pub at a different time.”

“I reckon to move from here, after 50 odd years in Millers Point, will just about see the end of me.”

“Boxing Day we used to take over Kent Street, we didn’t ask permission, we’d block off one end all the way up to where the Bridge is now, and we used to play cricket games.”

“My five children have fond memories of growing up here.”

The Sirius Building

The Syrius building was the focus of much of the protest; a high-rise, 79-unit apartment complex overlooking the Harbour Bridge.

It had long been a point of egalitarian curiosity, that some of Sydney’s poorest of the poor had the best views.

Sydney University lecturer Oliver Watts writes in his piece In Praise of the Sirius Building:

It is on the run to ruin that finally Sirius is telling its story most loudly. The empty shell of a building points to the failure of its 70s dream that even public and low cost housing should have a city water view.

Watts writes that the Syrius Building embodied the idea that social housing should be mixed: from the elderly to the young; from families to singles; from essential service workers including teachers and cleaners, to those on the pension.

The Sirius, by the architect Tao Gofers, is a product of its time. Built in 1979 — to provide public housing for people relocated from the Rocks during the time of the green bans — it lasted merely 37 years. Its failure communicates as much about society as its success.

Ruined space is ripe with transgressive and transcendent possibilities… They offer opportunities for challenging and deconstructing the imprint of power on the city. Tim Edensor.

There is a real generosity of spirit in this building, it is respectful of the residents’ original suggestions and it is built to the highest quality. Many in the architectural fraternity mark this period as the last when the architect, rather than the developer, led the project.

Many of the original residents of the Sirius would not have had, even beside the harbour views, any of its comforts before — from modern plumbing to new kitchens.

The last resident, a 90-year-old blind woman known as Myra Demetriou, was forced to pack her bags in January of 2018.

Myra Demetriou became the face of the campaign to save the historic housing block.

The social housing apartments were unanimously recommended for protection by the Heritage Council, but the Government had ignored that advice, putting the building up for sale to developers.

“It’s so ridiculous, I don’t know who they think they are. They say they need the money — they need the money like a hole in the head.”

In May of 2018 the Syrius officially hit the market, with a price tag north of $120 million. It was described as “Australia’s most valuable freehold land”, according to the international sales campaign that was kicked off by Savills Australia.

It Could All Have Been Avoided

There were already 60 empty houses at Millers Point when the pogrom began.

Most of those houses have yet to be sold.

Yet the State Government has mounted a determined effort to move the old public housing tenants on, uniting a once divided “community” whilst creating a wave of sympathetic media coverage.

Prior to the then Housing Minister Pru Goward’s announcement of the sell-off there were three community groups dedicated to fighting the rumoured sale of the suburb.

The sight of the scheduled six-star casino Barangaroo rising from the mud literally at the end of their streets was laying a deep unrest.

But none of the warring community groups could agree on tactics and no one had a good word to say about anyone else. That is the reality of the disenfranchised on housing estates. They squabble.

Then Pru Goward came along.

The groups united against a common enemy; and despite limited resources ran a brilliant social media and street protest campaign.

The media was on-side; and the organisers gave them all the material they needed to write “brutal conservative government attacks working class community” stories.

From overseas research uncovered in a standard literature search in their Social Impact Assessment, the NSW Government knew that resettling an elderly population, as at Millers Point, would lead to increased morbidity rates.

Key details were removed, including quotes from a Scandinavian longitudinal study that risk of death in urban renewal was ‘’one important implication we want to emphasise’’.

As The Sydney Morning Herald recorded:

The NSW government ignored warnings that moving elderly residents from Millers Point would increase their risk of death, and an official report was altered to downplay the potentially deadly effect of the public housing sell-off.

Documents obtained by independent Sydney MP Alex Greenwich under freedom of information lawsshow warnings about an increased risk of death were either removed or altered in a social impact assessment, commissioned by the NSW Land and Housing Corporation.

In other words, Pru Goward knew perfectly well that some people were likely to die as a result of policies she implemented, first in her role as NSW Housing Minister, then in her role as Planning Minister.

How does that not make her culpable? How is the work of her lieutenants in attempting to conceal the research from the public not a breach of the legislation controlling the behaviour of public servants?

Did Goward have the grace, dignity or plain old-fashioned common decency to come down to Millers Point and tell the people who lived there why their lives were being so mercilessly disrupted? To explain to them why it was important that their homes be sold from under them?

Of course not.

Did the then Leader of the Opposition John Robertson, whose party initiated the sell-off, stoop so low as to try and shore up votes amongst the beleaguered elderly; to come down to the Harry Jensen Community Centre in Argyle Place to assure them that the Labor Party would do all it could to help them.

Of course he did.

Housos with Million Dollar Views

Beyond providing a case study in appalling media management, for what not to do if you’re a departmental media masseur, there is much to be learnt from the debacle at Millers Point. In a sense it was a microcosm of all that is wrong with public housing in NSW.

Some of the people in this cluster of homes had never so much as swept their floors from the day they moved in.

They didn’t value the properties because they had no value.

They live next to one of the most beautiful harbours in the world, but barely ever so much as look at it.

“Housos with million dollar views” blared the headlines.

Some of them barely raised their eyes.

But whatever went wrong in their lives back then, back when, the people hosed out of the Rocks were leaving with nothing but their own bitterness, disillusion and sense of loss; despite the decades that some of them have lived there.

It was unfair on them. It was unfair all round.

The state government’s latter-day policy of dumping the mentally ill into Millers Point, rather than finding them appropriate accommodation, exacerbated the difficulties in the area.

For years the elderly had not felt safe outside their own homes. it was deliberate. They wanted these people out.

Public housing was meant to be a step up out of poverty, a way for working class families to get onto their feet and get into the private market, to better themselves. The people shuffled on from the Rocks were no better off than when they arrived. Public housing hadn’t lifted them up; it had barely worked to maintain them in a slowly deteriorating state.

It is in the housing estates that the rhetoric concerning the poor and the vulnerable creates a race to the bottom. It is here that the destructive rhetoric of victimhood has had its worst impacts.

There has to be a way where all the negatives of public housing estates, the concentrations of “social disadvantage”, their unsafe nature, the lack of care that the tenants take in their properties, the criminality and appalling malaise that characterises so many of them, could be turned around.

It is, after all, taxpayers’ money; and the taxpayer is entitled to expect that their money is being spent improving the lives of others, not making them worse.

One banner flying from a terrace balcony reads: “Why should only the Rich Live in the City? Working People Need Homes Here Too.”

But in truth a significant number of the people who inhabited Millers Point had little historic connection, they just happened to have washed up there on the tides of fortune.

The upwardly grasping middle classes who thronged the Rocks at the weekend, admiring, above all else, the real estate, often asked loudly as they eyed the less salubrious local housing tenants: “How do they do it?”

The answer was easy enough. People usually end up in public housing because something has gone badly wrong in their lives.

While the mythologising of a local “community” with historical links to the area struck a chord with many Sydneysiders, there were many who ended up in Millers Point by happenstance.

Apart from a few happy drunks at the bus stops, who made easy material for time-poor journalists, the flotsam and jetsam of misfits, the mentally ill and the dysfunctional also made up a significant percentage of the Millers Point population, but were ignored in the public narrative.

Manic Mansions

Yet another slate in the largely unwritten history of Sydney’s underclass was being wiped clean, without any documentation to prove who they were, or why they were.

These sometimes demented souls.

One of the apartment blocks, known not so affectionately as Manic Mansions, was inhabited by aging alcoholics, addicts, schizophrenics, squatters and ex-cons.

Wave a few hundred million dollars in front of developers and governments see what happens.

In 2014, Manic Mansions was already being emptied.

The squatter was made homeless with the assistance of the police.

The ground-floor alcoholic, whose windows had long been smashed and his doors broken, who hadn’t had the electricity on or paid rent in years, was relocated.

One of the building’s “Methadonians”, whose biggest task of the day was to make it to the Clinic to get his dose, was shifted on to housing in Surrey Hills. His old apartment remains empty.

Stimulated by the squatting actions by community activists, patrolling security guards checked the vacant apartments regularly.

A banner, only half unfurled, hung from one of the windows: “Save Our…”

A former bright, bubbly, successful union lawyer on the third floor had a three bedroom apartment with million-dollar views of the harbour all to herself.

Her downward slide had begun many years before.

She was found one New Year’s morning bashed at the bottom of the stairs, too drunk to move.

The author helped persuade her to get into an ambulance.

“Death can’t come soon enough,” she would say often enough.

She got her wish in 2018, four years on, at the age of 56.

By then all the former residents of Manic Mansions had been dispersed. The building itself was boarded up, with a development application stuck on the hoarding outside.

And the people who once lived there were, in a very real sense, little more than memories.

This is My Home

Number 11 Lower Fort Street, a grand Victorian Terrace known as Ballara, has five bedrooms and three bathrooms.

It is a double fronted four story terrace tucked in next to the southern end of the Harbour Bridge has views across to the Opera House from its front windows, and from the back views across to the yacht dotted Lavender Bay.

There is a jacaranda tree in the large backyard, and the views across to Luna Park are only partially obscured by Pier One.

It is a pleasant, easy walk to the Opera House, the Sydney Theatre and Dance Companies, the cafes dotting the finger wharves along Hickson Road and a number of fine dining establishments. In other words, in a real estate obsessed Sydney, it’s just about impossible to get a better location. And it can’t be built out.

Just up the private lane at the rear of these spectacular houses, spelt out in adjoining t-shirts hanging on a clothing line, are the words:

“THIS IS MY HOME”.

As the protestors and squatters disappeared, the $3.9 million Number 11 Lower Fort Street fetched at auction in mid-September of 2014 came to be seen as a bargain.

If one thinks of the houses as living creatures, they are better off being sold to people who have the financial resources to care for them, who will appreciate them.

But one of the savage ironies of the sell-off of Millers Point is that the prices they fetched, for some of the most stunning real estate in the country, is a comparative pittance to what could have been achieved with an orderly, dignified, civilised sell-off.

Denouement

Millers Point is quiet now, gentrification well under way.

The street crazies who spent their days moving garbage bins from one block to another, for no apparent purpose, or rustling up the energy to go rob someone in the city, are all gone.

The drunks who once gathered in protective groups no longer seek shelter at the bus stop have been moved on.

In the heart of the district, the Harry Jensen Community Centre no longer serves lunch for elderly residents.

A new community of the wealthy, ensconced in some of the best real estate in Sydney, have no need of welfare workers and humble $6 meals. Housing activists no longer use the hall for meetings.

But across Miller’s Point’s rich history, 2014 will go down as one of its most shameful episodes, with Planning Minister Pru Goward front and centre.

If you ever wondered where the heart of the NSW Government lies:

In 2017 Ms Goward was appointed NSW Minister for Social Housing.

John Stapleton worked as a staff reporter for The Sydney Morning Herald from 1986–1994 and for The Australian from 1994–2009. He has written many hundreds of newspaper stories centred in and around Sydney.

Tim Ritchie work at ABC Radio for more than 40 years, and still works in audio as Head of Podcast for The Parent Brand. He cycles each day from 4am and takes photos of Sydney empty, chronicling the changes.

No comments:

Post a Comment