From Little Things Big Things Grow

With special guest:

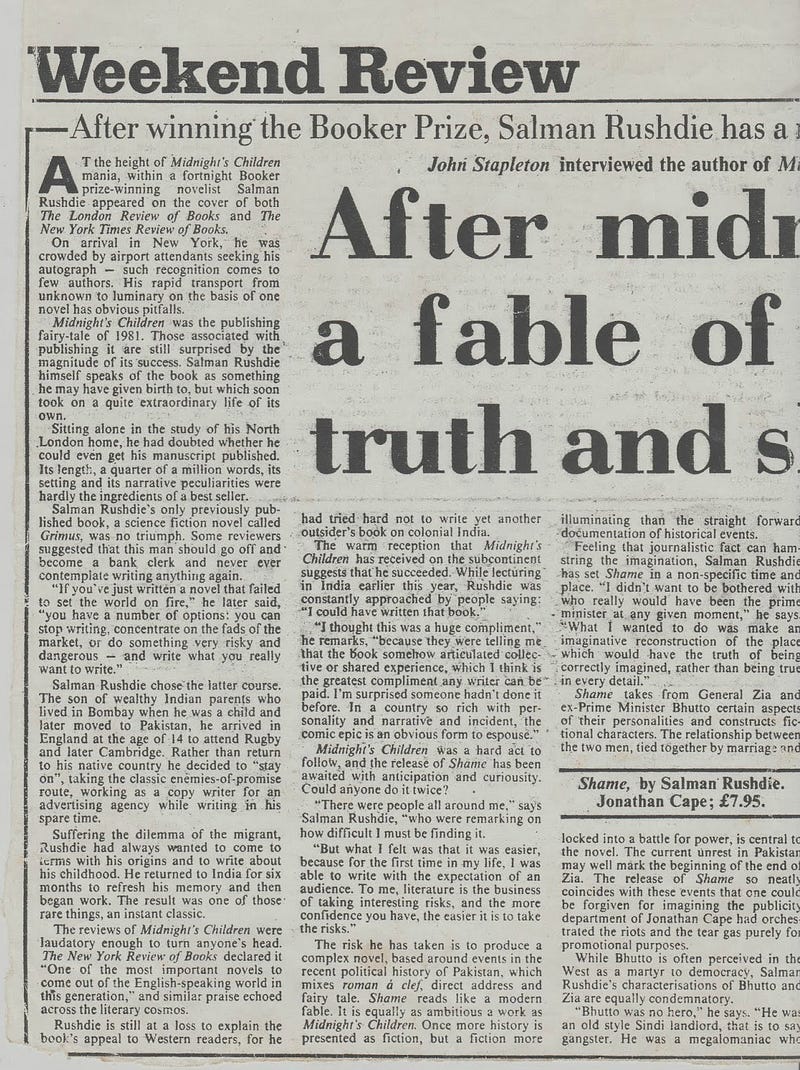

- John Stapleton

… in conversation with Bill Kable

John Stapleton is a legend at Dads on the Air. In the year 2000 while working as a journalist he became involved with a number of fathers who struggled to see their own children because of the machinations of the Family Court. Worse still, because of the legislation no-one in the broader community knew what was going on. So John resolved to shed some light on the problem through a community radio program run on a shoestring from 2GLF in Liverpool New South Wales after giving the program its name. Here we are 18 years later still going strong.

In this program John Stapleton tells us some of the history of the early days and then lets us know about his most recent venture a niche book publishing company called A Sense of Place Publishing. John has published his own books notably Chaos at the Crossroads and most recently a book by former Dads on the Air presenter Peter Van de Voorde called Children of the State. It is clear that the fire still burns in John about the many injustices fathers suffer silently.

It is a great pleasure for us to go back to the source and speak with John Stapleton who for many years was not just the voice but he also provided the media expertise and was the source for many of the stories brought to air.

Song selection by our guest: Wild Man by Kate Bush