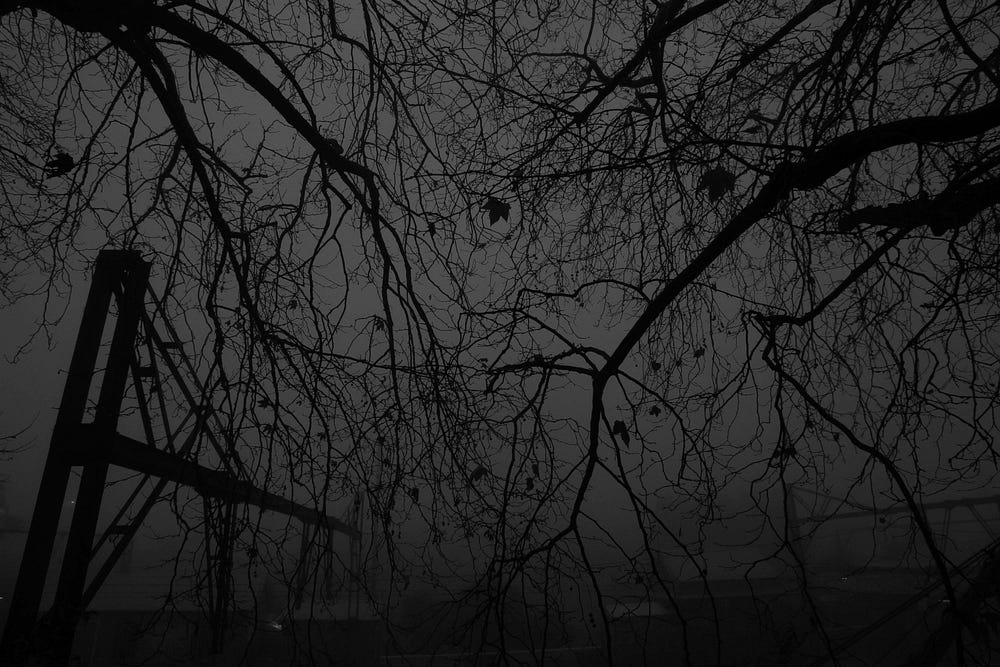

Wherever I have lived I have always documented my own immediate environs.

The photograph above is of my front yard.

You don’t get any more immediate.

There is an old quip about Katoomba: The Retired, the Retarded, the Retrenched and the Religious.

No one laughs but us.

Proponents call it the home of The Relaxed, The Rejuvenated, The Recharged and The Revived.

Oh sure.

Katoomba, a small town in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, is a unique place, rife with colorful characters.

It is a social welfare state.

The bookend suburbs are much more affluent.

It is what it is.

Through a Dark Glassily

Katoomba was built because of coal.

There is this old industry which is dying out, but there are the vestiges rattling through the place.

The station opened in 1874 as ‘The Crushers’, a stopping-place for trains with quarry men, equipment and wagons for transporting ballast.

There is still that feel, a place of toil and grinding work.

A place of finite dreams.

It’s damned cold in winter.

But there are always other layers.

There were historical train rides throughout this particular day, which marked the 150th anniversary of the Blue Mountains line.

The area was in severe drought.

The embers were flying out of these steam trains, and lit the litter on the side of the tracks.

The train stopped and this man, dressed in period costume, went back down the track to put out the fire.

My immediate thought: There is no indicator in this scene to suggest it is from the present.

The Winter Magic Festival

This image is of a young lady who was making her debut if you like into the steam punk subculture — which is based around the aesthetics of the industrial age.

Their adherence to this bygone imagery, their unique sense of the beautiful, is entirely intriguing within itself.

They dress in theatrical costume, there are lots of mechanics.

They reference the 19th century scientific romance of Jules Verne, H.G.Wells, Mary Shelley.

Victorian era. Early steam trains. Watches. Telescopes. Brass and iron.

It’s all about the way things once looked.

To define it is hard.

That’s true of a lot that happens here.

The Winter Magic Festival was cancelled this year because of all the new laws and regulations, traffic management, security.

The festival brought together all these subcultures, steam punks, furries, hippies, all sorts.

If not one of them, I have always felt a kind of empathic appreciation.

They are, if nothing else, aesthetically beautiful.

Beside the ratbags, there is a huge creative community up here.

Music is prominent, as are the visual arts.

Magic mushrooms grow throughout the mountains.

They once were an integral part of the Winter Festival. People believed in them, as if it was all part of a sacred ritual. We weren’t born yesterday.

After a 24 year history the Winter Magic Festival went into hiatus in 2018. Winter Magic attracts people from all over the world to celebrate the solstice on the shortest Saturday in winter.

With heightened concern across the country over the decimation of grassroots community events through ever tightening and excessive regulation, Katoomba locals say it has become harder and harder to stage the festival.

Myceleum: We are all connected

Most of the visuals which come out of the mountains are vistas, bluffs and things like that, the physical environment.

Chocolate box photography abounds; sheer cliffs bathed in beautiful golden light, there’s heaps of it.

Most people come up here for that.

These are the images tourists take away with them.

I think they bypass a lot.

We moved up here from Sydney.

I lived most of my life in Sydney’s inner-west. I had become tired, visually.

As kooky and interesting as that part of Sydney is, I had been walking the same streets for 30 years or more making photographs.

The upper Blue Mountains is a totally different aesthetic.

The Winter Of Discontent: It’s So Damn Cold Here

This is taken whilst out walking the dog.

Look at this place!

Visually I was attracted.

Straight away.

These are places people go to all the time, but rarely photograph.

Up here, you are subjected to different weather patterns than Sydney. We have a lot of mist and fog up here which is sympathetic to the architecture, flora, fauna.

And I tell you now, it’s always cold.

The cold eats into you up here. It comes up through the floorboards, through the window frames. You can’t escape it.

You have to learn to deal with it. Not everybody stays.

It is a mix up here. Visually. Socially. In the heart of everything.

European trees blend in with the native eucalypts. Rundown gardens adjoin estate grandeur.

That is the beauty. The wisteria outside wooden cottages in the spring. The narrow dark, inaccessible valleys the indigenous believed were deeply unlucky, where almost no one has walked in thousands of years.

There are fine remnants everywhere you look. Swiss chalets from the wealth that flowed out of Sydney during the 1900's, hidden estates from the earliest aristocrats of the colonies who wintered in the mountains to get away from the stifling coastal heat.

Plebeian and profound. Art Deco architecture. Old working cottages. Log cabins.

Back where we last were, we lived in brick boxes.

They Care For This Dripping Place

People around here bush walk.

They talk about the best vantage points. The state of the tracks. The places unexplored.

Outside the creative aspect of the upper mountains community, there is a staunch environmental component built into the people.

There are groups here who have their heads around climate change and the expansion of coal mines in the region, a concern to many of the people here.

A significant part of the Blue Mountains is World Heritage listed.

There is a lot of concern about development, including the new Badgerys Creek airport in Western Sydney, which would mean increasing flyovers and higher levels of visitation.

The raising of the Warragamba Dam wall, the main water source for the exploding population of Sydney, threatens to flood great swathes of the Blue Mountains National Park — drowning with it countless indigenous cultural sites.

Something Wicked This Way Comes

The mainstream media which I have worked for all my life can be restrictive in senses, with such time limits placed on things. Deadlines. It doesn’t always suit for the creation of great photography.

Often the best pictures we take are outside a time frame, they don’t always fit a roster.

A lot of the images in my series Katoomba Noir are very close to home, the front yard, the end of the street, the station at the top of the hill.

I tend to concentrate on my immediate neighborhood because assignments often take me elsewhere, other people, other cultures.

I should be able to apply what I do to where I live.

I am always behind the camera.

I am always taking images.

As I took images I liked, I began collating them.

After a while I started to see a common theme linking these images together, and I realized it looked dark, brooding.

But that’s what it feels like up here. I’m not saying it’s bad. It gives the place a lovely character.

Our immediate friends are artists, chefs, past roadies, solar panel installers, masseurs and amateur astronomers.

They are people who tinker.

We find them a big inspiration; in many ways. Everything we are involved in collectively, they contribute to that, and they are creative people.

But there is an underlying darkness. I don’t know where it comes from but it is there.

Dean Sewell made his name as a documentary photographer concentrating his gaze on the social implications of the new globalized world economy and the environmental consequences exerted by climate change.

Through his acute studies Sewell also explores the dichotomy between the urban environment and its human habitation. This sits in stark contrast alongside his more reserved yet apocalyptic representations of drought and fire ravaged landscapes.

Sewell was the back to back winner of the 2009 and 2010 Moran Contemporary Photography Prize for a work borne out of a three year study of the Murray-Darling Basin in Australia and the Sydney Harbor ferries.

He has been the recipient of three World Press Photo Awards in 2000, 2002 and 2005 for works covering the transition of East Timor to an independent state, Australian Bushfires, and the 2004 Tsunami aftermath in Aceh.

Sewell was awarded Australian Press Photographer of the Year in 1994 and 1998.

In 2005 and 2008, Sewell’s art practice has seen him awarded artist residencies in the remote gold-mining town of Hill End, a town famous as a haven for artists in the post-war era.

Sewell’s works are regularly exhibited in leading Australian and International galleries.

He is a founding member of the photographic collective Oculi.

No comments:

Post a Comment