The Triumph of Death

Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

© Museo Nacional del Prado

Death triumphs over the mundane. An army of skeletons raze the Earth. All life is extinguished.

The background is a barren landscape in which scenes of destruction are still taking place. In the foreground, Death leads his armies from his reddish horse, destroying the world of the living. The latter are led to an enormous coffin with no hope for salvation. All of the social institutions are included in this composition and neither power nor devotion can save them.

Every inch of The Triumph of Death features chaos on a massive scale. It is as though the artist’s brush cannot keep up with the fanatical energy of death’s hordes, busy killing and harrowing wherever you look.

In the foreground, a skeleton is cutting a man’s throat while not far away a starving dog eats a woman’s face. On a hillside further back on the right, a dead man has been skinned and hung from a tree. His head is thrown backward and held in the branches by a metal pin that passes through his skull.

Richard B Woodward. WSJ.

The Triumph of Death, once the property of the Queen of Spain, has been in the Museo Del Prado in Madrid since 1827.

It is now in Vienna, at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, especially restored for the largest exhibition of Pieter Bruegel’s work ever held.

The exhibition is badged as Once in a Lifetime. For once the oft repeated phrase, heard thousands of times in far more ordinary circumstance, is correct.

The size of the exhibition, the substantial resources dedicated to it, and the high level of expertise involved all ensure that.

Museums and private collectors count Bruegel’s works among their most precious and fragile possessions. Most of the panels have never been loaned for an exhibition.

Dulle Griet

1563, panel, 117.4 × 162 cm

Antwerp, Museum Mayer van den Bergh

© Museum Mayer van den Bergh

Dulle Griet, also restored especially for the exhibition, pictures an army of women being led to pillage hell. The restoration revealed that the work was painted in 1563, two years later than originally thought. Previously the signature and the date on the painting had been illegible.

Eighteen years. That’s all Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s remarkable burst of creativity lasted. And we’re still talking about him centuries later.

The Vienna exhibition commemorates the 450th anniversary of his death.

During his lifetime, Bruegel was among the period’s most sought-after artists, with his works achieving exceptionally high prices.

But like Shakespeare, despite his contemporary fame little is known about his personal life, including the exact date and location of his birth.

Only about forty paintings and sixty prints by him have survived.

By bringing together over 90 works by the master, the Vienna exhibition has assembled for the very first time a comprehensive overview of Bruegel’s oeuvre: comprising around 30 panel paintings, that is three quarters of extant paintings.

Also on display are almost half of his preserved drawings and prints.

This week a symposium at the Kunsthistorische Museum, The Hand of the Master, which will focus on material and technical aspects of the work, brings together some of the world’s most renowned Bruegel scholars, conservators, and scientists.

Bruegel revolutionized landscape and genre painting, and his compositions continue to elicit varied and controversial interpretations.

Sometimes referred to as Peasant Bruegel, the depth and breadth of his pictorial world, his the powers of observation and unique narrative abilities deployed in his depictions of everyday life continue to fascinate.

All papers presented at the symposium will be included in a 2019 essay volume published by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in collaboration with Hannibal Publishing.

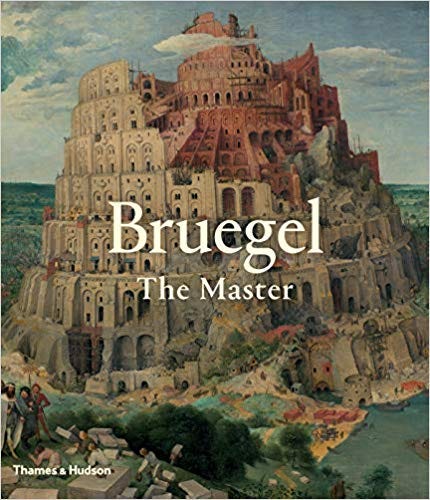

The catalog has just been published as a standalone title, Bruegel The Master.

Inside The Battle between Carnival and Lent

The Battle between Carnival and Lent

1559, oak panel, 118 × 164,5 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

On his deathbed, Pieter Bruegel the Elder beseeched his wife to burn a series of drawings he feared were too inflammatory.

The subversive — and, to this day, little-understood — qualities of Bruegel’s work often took the shape of panoramic landscapes dotted with bursts of everyday activity. Alternately interpreted as celebrations or critiques of peasant life, Bruegel’s paintings feature a pantheon of symbolic details that defy easy classification: A man playing a stringed instrument while wearing a pot on his head could, for example, represent a biting indictment of the Catholic Church — or he could simply be included in hopes of making the viewer laugh.

Meilan Solly. Science Journalist. The Smithsonian Magazine.

The Battle Between Carnival and Lent sets up a battle between the sacred and profane, between the pious and the beer drinkers.

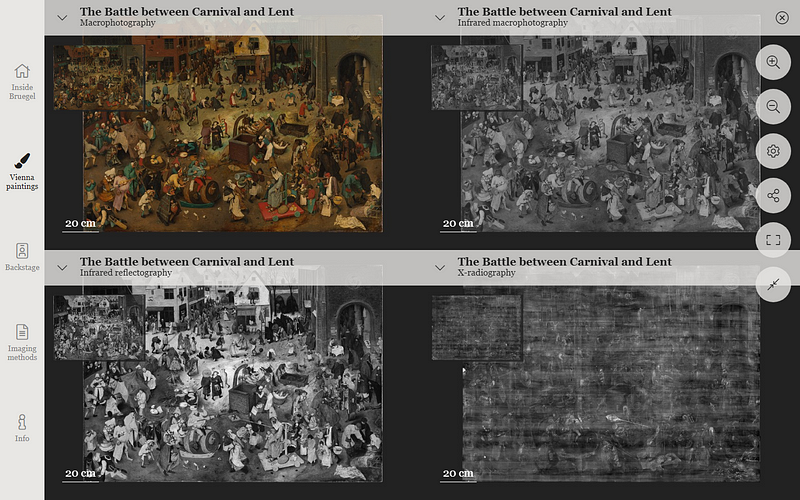

One of the many remarkable things about the Vienna exhibition is that researchers, amateur sleuths and the curious can all, through X-Ray and Infrared photography, examine Bruegel’s paintings in unprecedented detail.

“Inside Bruegel,” launched with the support of the Getty Foundation, which will continue to be publicly available after the Exhibition closes. It is an ambitious restoration and digitization portal launched to coincide with the Bruegel retrospective. It aims to uncover the Renaissance painter’s underlying intentions.

The Conversion of Saul

1567, oak, 108 x 156 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

The website features high-quality renderings of the Vienna institution’s 12 Bruegel panels, as well as scans of the details hiding below the final brushstrokes.

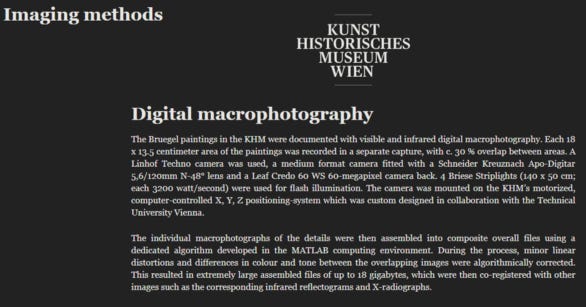

In addition to allowing visitors to take a closer look at Bruegel works as they’re known today, the portal features scans conducted with infrared reflectography, macro-photography in infrared and visible light, and X-radiography, affording scholars and art lovers alike an unprecedented glimpse into the artist’s creative process, handling and technique.

Infrared photography makes signatures and under drawings visible, while X-ray imaging allows researchers to examine the wooden panels on which Bruegel painstakingly layered his creations.

For the technically minded:

And this is what the portal looks like:

X-ray imaging of a 1559 work, “The Battle Between Carnival and Lent,” reveals macabre features masked in the final product, including a corpse being dragged in a cart and a second dead body lying on the ground. Infrared scans further highlight the small changes Bruegel made prior to completing the painting, with a cross adorning a baker’s peel transformed into a pair of fish. The cross blatantly refers to the church, while the fish — a traditional Lent delicacy — offers a subtler nod to Christ.

Meilan Solly. Science Journalist. The Smithsonian Magazine.

Bruegel’s oeuvre endured much over the centuries.

Some were heavily cropped or even painted over.

Someone took a saw to the top and right hand edges of the famous The Tower of Babel.

The corpses seen in the X-ray version of The Battle Between Carnival and Lentalso offers evidence of later artists’ interventions.

Bruegel didn’t cover up the dead bodies himself; instead, an unknown person likely blotted them out during the 17th or 18th century.

The Peasant Bruegel

Bruegel’s works have been arranged both chronologically and by theme, allowing visitors to study and appreciate his stylistic development and the impressive variety of his oeuvre.

The galleries showcase both his masterpieces and series and groups reunited for the first time in centuries; in the smaller adjoining rooms are presented the findings of recent comprehensive technological analyses, offering new insights into the works’ evolution.

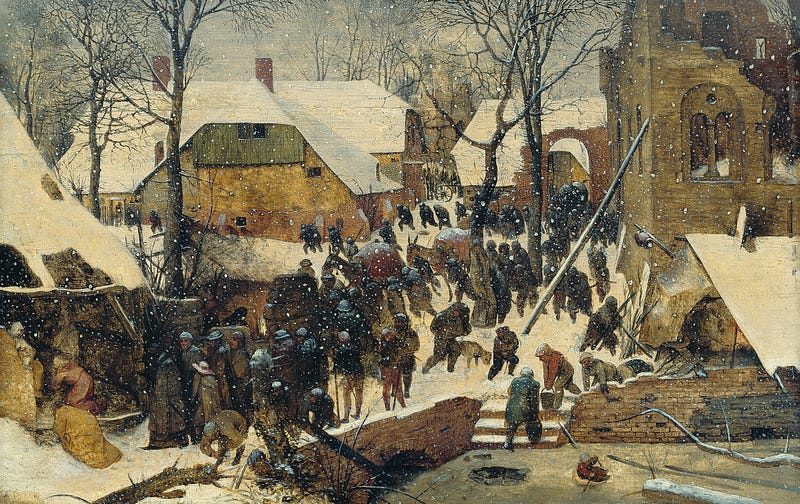

The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow

1563, wood, 35 × 55 cm

Swiss Confederation, Federal Office for Culture, Collection

Oskar Reinhart ‘Am Römerholz’, Winterthur

© Collection Oskar Reinhart ʻAm Römerholzʼ, Winterthur

Highlights of the exhibition include The Haymaking from the Lobkowicz Collections, Prague, View of the Bay of Naples from the Galleria Doria Pamphilij in Rome and Two Monkeys from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

What would have happened if Pieter Bruegel lived into old age?

It is thought that he trained in the studio of Pieter Coecke van Aelst in Antwerp and was also instructed in the art of miniature painting by the latter’s wife Mayken Verhulst. In 1551 he was admitted as an independent master to the Antwerp painters’ guild.

From 1552 to 1554 he traveled through France and Italy.

From 1562 he mainly worked as a painter. In 1563 he established himself in Brussels, where he died in 1569.

But in some sense he defied death to confound the future.

As the curators of the exhibition declare, hardly any other artist has undergone such changes in identity over the centuries: from the ‘new Bosch’, ‘Peasant Bruegel’, humanist, moralist or Christian painter to satirist and social critic. Now they just call him ‘the Master’.

The Haymaking

1565, oak panel, 114 × 158 cm

Prague, The Lobkowicz Collections, Lobkowicz Palace, Prague Castle

© The Lobkowicz Collections

Sabine Haag, General Director of Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, says Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his work have attained a legendary status in our collective consciousness.

Anyone interested in art knows the name Bruegel.

The most important Netherlandish painter and draughtsman of the 16th century had already achieved great fame during his own lifetime, but was largely forgotten in the 18th and 19th centuries and only rediscovered by art historians in the early 20th century.

His variety of subjects, which draw on the earlier pictorial traditions of Hieronymus Bosch and the latter part of the Middle Ages, and their originality of execution, still elicit great fascination from viewers today.

For their generosity and great faith in entrusting us with such fragile works — all among the most precious holdings of their respective collections — we extend our wholehearted thanks to the numerous institutions and lenders from around the world who have contributed, and who have collegially and constructively supported this project.

The Return of the Herd

1565, oak, 117 × 159 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

In a joint statement the distinguished curators, drawn from a number of leading institutions, declare the Bruegel Exhibition “an absolutely unique event”.

It will be the very first time ever that the full range of works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder will be on view. More than half of his surviving paintings, drawings and prints will be reunited, works that only leave the walls of the museums that house them on the rarest of occasions.

An exhibition such as this therefore ranks among the most extraordinary museum events, and it will most likely not occur again within this century.

The Suicide of Saul

1562, oak panel, 33.5 × 55 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

The exhibition is based on a broad research project on Pieter Bruegel the Elder, a seminal but enigmatic figure whose pivotal role in the pictorial inventions in regard to landscape and genre is widely accepted.

The meaning of many of his works, however, is still hotly debated, and very little is known thus far about his creative process, how he went about in the making of these hauntingly beautiful works.

We repeatedly seek new paths of access into the work of this great master.

An acute observer, Bruegel often holds up a mirror to the viewer, something that makes his work highly immediate and sometimes unsettling, thus giving it a fascinating connection with the here and now.

No comments:

Post a Comment